A Dream of Caligula’s Horse

Who wast Thou, O Caesar, that Thou knewest God in an horse? – Aleister Crowley

Whatever happened to Incitatus, the horse whom the mad emperor Caligula famously appointed to the Roman Senate? We know nothing about his origin or pedigree, nor do we know when or how he died. After his master’s assassination, Incitatus disappears from both history and legend. Senators are notoriously venal characters, so it is easy to imagine them flaying their former colleague with gusto and tossing his remains to the dogs. Where the wealthy are concerned, their irony is never as inventive as their will to self-preservation.

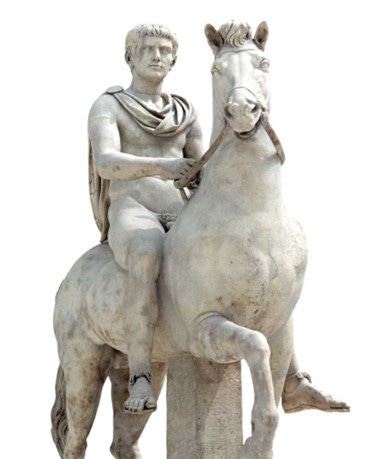

For every great man, a horse. Alexander had an Akhal-Teke, of Turkoman descent, named Bocephus. Julius Caesar’s horse was Austurcone and, unusually, he had a cleft foot, which became the source of much prophesying. When he died crossing the Rubicon, Caesar had his equine steadfastness memorialized in marble. During the Night of Power, the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven on the back of Buraq, whose name means lightning bolt but also infers unique blessing. Husayn ibn Ali’s Zuljanah took an arrow meant for his master, and Persian art never forgot this brave animal’s devotion to the Holy Imam. Napoleon had fifty-two horses but only one Marengo. He died in 1831, after accompanying Bonaparte at the pivotal battles of Austerlitz and Waterloo. Simon Bolivar’s horse, tall and grey, was named Palomo, ‘pigeon.’ Foretold in a dream wherein Bolivar’s wife gave birth to a foal, Polomo dutifully appeared on the battlefield of Boyacá. El Cid expelled the Moors, ushering in a long period of stupidity in Europe which has yet to pass. When the Cid died at Valenia, he was tied to his beloved Babieca to convince the enemy that he still led the troops. Garibaldi, a passionate lover of all animals, doted on his Marsala. As inseparable in death as they were in life, they rest near each other in the private gardens of “Il Eroe dei Due Mondi.” And no tally of horses and power would be complete without Er khoyor zagal, the favorite twin stallions of Genghis Khan. Without the horse in general, the Golden Horde would have gotten nowhere.

For obvious reasons, lists of great horses and horsemen never include Incitatus and Caligula. Yet Caligula’s notorious excesses may have been an historical smear campaign, dating from later authors such as Cassius Dio and that old gossip, Suetonius. Historian has always been a sleazy profession. Decadent period classical hacks gave their readers salacious pulp, mixing the pleasures of the lusty bodice-ripper with ultra-violent gory thrills, all cured in the gruel of history and recounted with mock indignation. Whether the bloody stories contravened contemporary record or not, Caligula became a personification of corrupt absolutism and a testament to the superiority of the republican system over a louche and degenerate monarchy. But was he any worse than the other emperors? Who said Caligula was so awful and, most importantly, what did they want to protect by saying it?

The answer is oligarchic power. An avowed populist, Caligula stood in opposition to Rome’s landed monopolists, bloated aristocrats who sought to engorge their estates on the public purse and demanded that the emperor to rubber-stamp every hostile takeover and oppressive tax law they presented to him. This network of lawful commodity extraction was created by the private power of the Senate; a monarch disrespected it at his own peril. In lieu of an actual revolutionary, the Roman people identified with Emperor Caligula because of his vocal hatred of the landlord class. His greatest ‘excesses’ lay in the public humiliation of the Senatus Populusque Romanus, a corrupt institution which had become an advocate for rentier interests in the courts of the Curia. Appointing Incitatus to this most august body was an ironic barb leveled at a financial elite which ruled Rome as an iron creditor—also as a jailer, to whom, as far as the wretched poor were concerned, no bribe was ever affordable and no appeal ever possible.

In addition to Incitatus’ senatorship, several other events are cited as evidence of the emperor’s madness. Let us examine the most infamous of them, veracity aside: Caligula declared war on the god Neptune. He took his armies to the coast and commanded them to carry off shells and waterweeds as booty; then the legions and their lord returned to Rome. Caligula claimed a victory, however ludicrous, without losing or taking a single life. His point is crystal clear: every military triumph is symbolic and subject to time, which erases glory like waves erase the shore; the spoils of war are valuable to those who instigate wars—for everyone else, the price of this primitive accumulation is calculated in expendable lives. Caligula was criticized as a coward for not attacking Britannia during the spring of AD 40. But if he went against the advice of Senate hawks and their lickspittle generals, it was because he knew that the invasion would be futile. After all, the Brass and the Experts are dead wrong every time (See Stalingrad or Vietnam or Afghanistan). Caligula may have averted a catastrophic failure of imperial overreach and hubris, similar to the Punic Wars that had almost destroyed Rome a hundred and fifty years prior. In BC 55, almost within living memory of his reign, some 20,000 legionnaires of the Roman Republic had been utterly wiped out by the Parthians at the Battle of Carrhae. The memory of these atrocious defeats lingered in the public mind, if not in the shame of the Senate. Caligula’s one actual miliary act was the removal and execution of Ptolemy, petty despot of Mauritania, in AD 40. No central power can tolerate a parallel state, so Caligula’s action can be considered pure realpolitik, a necessary purging of a mafia-like entity which might one day become powerful enough to challenge Rome.

In comparison to the more celebrated emperors, Caligula’s foreign policy was remarkably pacific. In AD 39, he deified himself. Given his prodigious grants of general bonuses and his apparent aversion to war, he must have looked like a benevolent and peaceful god to the army conscripts. It was they who had nicknamed Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ‘Caligula’, or Little Boots, when he was a child, a sobriquet which never embarrassed him and by which he is still known today.

Finally, we come to Caligula’s incestuous liaison with his sister, Drusilla. Why should Caligula conform to middle class morality? Didn’t the senators pimp their own family members to gain property or curry favor, often to men they despised and knew to be brutal? Caligula seemed to have genuinely adored his sister, whatever their relationship [i]. He declared her his co-regent on the throne of heaven, and after she died of fever he was inconsolable. The chill forces of the aristocracy closed in while his power slipped; omens multiplied like stones. As the doomed emperor wandered alone under the grand aqueducts baring his name, grief opened the jaws of a dusky and implacable summer. Give me the waters of Lethe that numb the heart, if they exist, I will still not have the power to forget you. (Ovid)

There are conflicting reports about Incitatus’ rank. It is said that the horse was appointed as a consul but also entered the priesthood; several sources maintain that Caligula himself circulated such stories and the historians regurgitated them later as proof of his demented venality. Robert Graves gives a moving description of Incitatus’ retirement in his novel, Claudius the God (Emperor Claudius is speaking): Another leading senator that I degraded was Caligula’s horse Incitatus who was to have become Consul three years later. I wrote to the Senate that I had no complaints to make against the private morals of this senator or his capacity for the tasks that had hitherto been assigned to him, but that he no longer had the necessary financial qualifications. For I had cut the pension awarded him by Caligula to the daily rations of a cavalry horse, dismissed his grooms and put him into an ordinary stable where the manger was of wood, not ivory, and the walls were whitewashed, not covered with frescoes. I did not, however, separate him from his wife, the mare Penelope: that would have been unjust.

A dream

After reflecting on the life and times, and watching the sterile ‘restoration’ of Bob Guccione’s 1979 pseudo skinflick, Caligula, I sank into a dream. This dream was like a movie—as if I were watching a film being projected, but also on the set contributing to its production. Sometimes I was an actor, yet I was also one of the real historical figures observing the actors on screen. I may even have been Caligula himself, or perhaps a part of his psyche incarnated in a separate objective form. It is hard to remember for certain; empty men like me are notorious in their dreams because our freedom begins and ends there. But I am sure that the role of the horse was strictly off-limits. Incitatus was directing the whole spectacle to set the record straight. Upon waking, I wrote it all down:

Cloud follows cloud, sea funneling into cloud, full fathom fire and charm, letters drilled into the sky; the sound of hammers and neighs, sounds of blood pouring into brambles; the moon is pressed into a wax stain, dying light and brittle frost crack the morning grass:

I-N-C-I-T-A-T-U-S

After the death of Caligula, Incitatus wanders around the bloody scene. Smoke, pyres, sounds of the soldiers executing the consorts and favorites of his late Divine Imperial Majesty. The horse ruminates, Voice Over:

Swine. They grind up these men and women who only did what they all do: ingratiate themselves, betray their friends, scoop up tail, expand their holdings. The Praetorian Guard are busy. This might be my last charge. Aulus the Briton runs the glue factory and he always had his eye on me. Beady-eyed, resentful… A horse is a horse, of course, of course. Britons eat horsemeat.

Incitatus passes by his statue, reflected alongside his statue’s upturned reflection in a red pond:

The same people who erected it will pull it down. And in its place, a statue of the conspirator, Cassius Chaerea? Until he gets the chop. Don’t trust your tribunes and comrades, Chaerea… The nobility knows the king must die, but they can’t let the direct instrument get away with it. That’s why Caligula killed Macro who killed Tiberius. Most of all the rich love velocity—the speed of going back to the status quo. They just switch the heads. Every statue has been Janus at least once. Chaerea hated Caligula because he made him say ‘Priapus!’ as a password in that fey, falsetto tone he was born with. People laughed. You couldn’t forgive that, Chaerea, so you struck the first blow. Your voice finally acquired a little bass. Soon you will sing your own funeral song with some real soul.

Drusilla tucks Incitatus into bed. The three of them—her, the horse, her sovereign brother—doze in an endless afternoon.

I would rather be galloping, hon. Strange services here. Yet your hands are soothing and your brother, cupped in your arms like a plant, lazily feeds me apples covered in treacle. I’d feed on your sweetness if you were a mare. And I was indeed to father centaurs, but the emperor got cold feet when his wife offered herself up way too quickly. This kingdom makes fantasies in my head because it is itself fantastic. Days follow days, but the entrails do not read happily. Drusilla’s legs are serpents, tributaries, warm knots. She loves both her brother and me. Neither of them see the raven above the bed. The animal world does not accept symbols, and it is more beautiful and more cruel than feeble human magic. Caligula is an amateur when compared to the fire ant. Compared to the intricate galleries of the honeycomb, Rome is a pile of clay and snot.

Caligula speaks in the deserted halls of the Senate:

Finest of steeds! Your nosebag must be taken from you lest you eat the whole supply, but it’s just your nature. You are incapable of true greed. You have carried me unthinkingly, like you would carry my grossest enemy. Weight is weight. Your fellow senators let only the weightiest ride them—that’s their burden. Is your trough empty? You would still carry me. You would starve to death, and carry me. Collapsing, carrying till the end. But these men? I know their wives and they give me their daughters (and sons and granddaughters). Senator Incitatus is wild in field and pasture, never wanting to own a single hectare. Your colleagues in this House won’t set foot on a property unless they have its deed, have swindled the deed, for fear of offending property and propriety. They are slaves. I am free. Incitatus is free. You are all manure on his hoof. I have spoken. Shut up! Now cheer!

Horsily, Incitatus shakes his head. The ghosts of the Senate applaud. The room starts to fill up with quiet, bent men as the canned applause fades down on the soundtrack. Heads fall from statues, rolling charcoal black on the pavestones. CUT to black. A woman screams.

FADE UP to Incitatus walking the streets of Rome, Caligula on his back. The city is kaleidoscoped in shards of mosaic, burnished brass; sunlight strikes these million Roman fragments. Horse and ruler walk on a glass ocean, the city beneath them is like a museum display. This glass ocean shatters, and the two walk on in blue space.

No wonder they love us. We give them games, at least. What else is there? I know I carry a clown on my back. So do they. But they also know about empty tables, about living to the ripe old age of twenty-six. They know the brutality of legionnaires who, drawn from their ranks, prey upon them, laughing with the taxmen and making free with the mace of law & order. They see the dark emissaries from great houses who spy upon their young ones and take these young ones off for pleasures in unconscionable rooms. In deep red rooms high up in the towers, the little ones are never heard from again. They recognize empty grain silos and looted storerooms, accidents and crop failures, while quail eggs pass by in cartloads heading to the suburbs.

But the gladiatorial fests are still free. Entertainment, vicious maybe—but at least the captive gets a fighting chance. And they are always on the side of these barbarians kidnapped from subjugated lands, always waiting for them to best the powers that be—and always appreciative when Caligula, who despises the same bourgeois bastards as they do, spares the life of some grubby Gothic victor, while the Senate scowls because they placed their bets on a well-trained champion educated in their schools. So it’s all emotion. Naturally. I hear a young man cry out Hail Caesar! while his mother clasps him to her breast. She would do the same for Caligula. He might even let her, for a moment or two.

Incitatus is in his dotage. The conspirators killed the wrong horse. Claudius is now Emperor. He refuses to strip Caligula of all honors, knowing that this would set a dangerous precedent. Though he feared and hated his nephew, Claudius trusts the Senate and the landowners about as much as Caligula did. Incitatus passes by numerous Japanese screens depicting quiet, country landscapes, until he stops before a particularly serene image. The former statesman starts to graze. He is on the estate of Proconsul Lucius Sergius Paulus, located in Augusta Taurinorum. Slow fade down over Voice Over:

I am old. I do not miss the palace or that ghastly manor Caligula built for me on its grounds. I celebrate the long grass and sniff the slugs. No one is interested in riding me anymore. The other horses have forgotten I was the emperor’s favorite and so, they have de facto forgiven me. I am starting to forget as well. But dimly, I see the shape of my old boss in his golden raiment or his Jupiter wings or covered in blood on the steps of the Palatine Hill. These figures are all the same to me. Time is a spool, curling backward and forward and all personalities in time are no different from one another, no different from the wilds, buildings, and beasts that are part of a longer duration than Man. All of it floats downsteam with a milky haze, images on the face of the waters. Rainy waters flow down to this farm, in this green place whose name will be shortened to Turin and whose future is the same as the past and present of Rome or Carthage or Mount Olympus. I have descendants. I do hope that they will know mercy, that they will find a kindly soul to shield them from that stony hand of humankind so easily raised in anger.

One day, rich men will raise the jeweled barges of Caligula’s which the Senate sunk. The emperor dedicated them to the moon and personally took the helm, gliding along Lake Nemi at night and offering libations to Diana, while people admired the gold figureheads and the thousand lights hanging from their sails. On the floor of one of them is a mosaic which shows me taking a flower from Drusilla’s beautiful long fingers.

[i] The incest charge was not contemporary with Caligula, appearing only in later salacious accounts of his life. Even Suetonius, who allowed almost anything into his gonzo accounts of Late Rome, called the charge ‘hearsay.’ And Caligula’s cotemporary, the famous orator and poet Seneca who was no friend of royalty, doesn’t mention it at all.

Another apocryphal story states that Caligula, sick with his own fever and convinced he would soon die, was on the point of naming his sister as his successor. Drusilla, Empress of Rome! But he recovered.

Good one Martin! Loved it