In 1926, the Mennonites arrived in Paraguay. Canada and the Soviet Union had earlier expelled them, but Paraguay offered refuge. The sect settled in the Chaco, a semi-arid region which can still boast of a population of jaguar, puma, and giant anteater, diverse vegetation which has adapted itself to the dry climate, streams full of piranha, and extraordinary beasts like the Waxy Monkey Tree Frog. It must have looked hellish to the new colony, but the Ayoreo peoples had lived there for eons. For them, it was the irreplaceable center of their physical and psychic reality. Every weed and rock was a cathedral and every insect chorus a chorus of angels. Though the area was sparsely populated given its vast size, the Mennonites lost no time in converting the heathen.

In addition to revealing the True and Living God, the religious used the natives to clear brush and raise cattle. A decade later, this produced a wealthy Mennonite ranching class. Mennonites have a history of environmental rapine in the Americas. They are also mobile vectors for disease. In Paraguay, they killed off untold numbers of Ayoreo with German measles, among other European plagues. Such biological accidents are how evangelical pacifists wage holy war.

It was not the first invasion of the Chaco. The Jesuits opened San Ignacio de Zamucos in 1720s, but it was so unsuccessful that the Ayoreo were ignored soul and body until 1900. Both Catholic and Protestant missions began a fresh assault; the Mennonites proved the most vigorous. Standard methods of child kidnapping were employed, as well as conscripting Ayoreo to ferret out their own people in the bush as the labor force thinned. Whether in the US or Australia or South America, the blueprint never varies. Afterward, every atrocity becomes just a tragic miscalculation. Late apologies are bitter fruit, rotten through.

As the cold machine of civilization grinds on, bodies are measured and indigenous tongues are recorded in dictionaries. Anthropological work always accompanies violance and population transfer. There were academic disputes on what to call the Native peoples of Paraguay and to which language group they belong. The Ayoreo must be gratified that the matter is settled: they are of the Zamucoan language family. The name Ayoreo is generally used today, but they have other names: Ayoré, Ayoreode, Guarañoca, Koroino, Moro, Morotoco, Poturero, Pyeta Yovai, Samococio, Sirákua, Takrat, Yanaigua and Zapocó.

The name Ayoreois translates roughly as “true people” and the related proper noun Ayoreode means “human beings.” The Ayoreois call the settlers, no matter their origin, Cojñone. This noun in English means ‘People Without Correct Thinking.’ Other English cognates might be Lunatics, Thugs, or The People Who Don’t Get It. For the Ayoreois the binary division is clear: there are human beings (Ayoreo), and then there are all the Others—empty shells who are strangers to the Chaco and to their own minds. Is there a more elegant yet decisive equation of the indigenous vis-à-vis the invader?

The Cojñone rarefied his plans when he insisted on assimilation rather than annihilation. If one refusenik Ayoreo remains, the rejection of civilization lives on with him. This is a dangerous idea. Today, there are estimated to be about 150 holdouts, the ‘uncontacted’, still living in the bush. The more guilty-minded Cojñone question even this number, but have declared finding them to be a priority, a race against time (strangely, it has also been suggested that the fugitive bushmen are just a rumor). These last people are apparently lying low in what is one of the last remaining wild areas of the Chaco, thanks to deforestation and the fad for ecotourism.

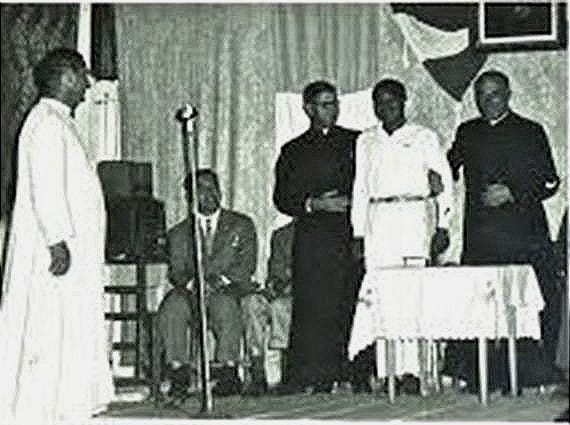

The Chaco War, 1932-1935, brought thousands of Paraguayan and Bolivian soldiers and more new maladies to the Chaco. Both sides mistrusted and used the natives. Under the Stroessner dictatorship [i], the Ayoreo were displayed like animals for public edification. Below is a picture of José Iquebi on stage in the 1960s, flanked by the missionaries whom he was forced to serve in the role of a liaison. Lassoed and kidnapped while hunting when he was twelve years old, he was taken to the capital of Asunción to be saved and then displayed as an example of the barbarous condition in which his people were mired. “They treated us like animals”, he recalls, now aged 85. And Mr. Iquebi also remembers the last Ayoreo redoubt in the Chaco, a “paradise”, having been used as a meeting place during the yearly draught since time immemorial.

The Ayoreo have fought a centuries-long war against various Cojñone powers: missionaries, loggers, corporations, privateers, fascist militia, NGOs, car manufacturers. But lately it looks like the white man’s insatiable curiosity has run out. The indigenous are no longer worth showing in circuses or broken down into words for books. Private property demands the raw brute force of radical clearances. So the citified natives have no other choice but to find their uncontacted brothers before the murderers do. The somber fact is that both the killers and the urban relatives of their victims must work toward the same goal: locating those who refuse to live like us. When this is accomplished, a way of life will come to an end.

As it is still disputed whether the so-called uncontacted exist it all, there arises an intriguing possibility: that the whole thing is a myth created by the Ayoreo to inspire resistance and confuse the colonial project. After all, the settlers, even in their ‘benevolent’ mode—medicine, land reservation, equal rights—are still the same old predator drones. El Dorado is forever in their sights. Given this dark state of affairs, the seductive idea of isolated Last Men from another epoch might be is a ruse to undermine the imperialist vision of time and place, a crucial intellectual stance to which everyone subscribes regardless of their position on the natives.

The savages are refugees, but refugees from the future. They are a stubborn and persistent reminder that history is not a progression but rather a series of wakes, eccentric circles, lacunae, lurches and lags, leaps and repeats. For the governing state, the wild Ayoreo are errant phantoms of prehistory. Yet their world is returning, whether we Cojñone notice it or not. The wilderness is part of the city: an overgrown lot, collapsing walls and rivers bursting their dams, the apparition of a coyote in the street. The natural world has nothing but time—so it has everything. And it is precisely these men from the dawn, as we call still them, who will go from the lowland Gran Chaco to the towns and cities recalling the lives they once led, retaining a studied agility along with the staid refusal of internal integration, to become a new kind of person who is neither a relic of the past nor a statue of the present. One day they will pass over our graves.

Another possibility, an alternate course of action: The uncontacted will simply elect to to disappear. How could we understand this, we who are taught to see survival as strength rather than a weakness? Without any sovereign decision, survival is simply a passive exhibition before invisible odds. There are precedents for choosing to die off rather than fade into an indistinct mass, walking like all the others through anonymous cities crowding one’s ancestral land. I do not accept your gift of survival. I accept neither the terms nor the bargain. Going my own way, I will vanish into a place you cannot comprehend. No more dictionaries and reports—the past and present have written me out because I forced the issue. I am Ayoreo and in the time of the Ayoreo.

In media stories about this case, we are shown blurry pictures of men running with spears in the underbrush. This is the image we have of the hunted remnant of Chaco—men made to resemble Bigfoot. Maybe they truly are members of the final 150, dodging the guns and cameras, caught in an unlucky moment. But I suspect that the decision, whether to enter into the mortar world or reject it, to join again with the relatives or abide unto the last, rests like all other important decisions with the only ones who can give life and as such, truly understand the stakes involved. The only ones who know the laws of death and rebirth, who grasp the wager and the price—the women.

[i] An avid participant in the CIA’s notorious Operation Condor, Stroessner lauded his overstuffed German heritage and made Hitler’s birthday a national holiday. Even more notoriously, he welcomed members of the SS after the war and hid Mengele, the Auschwitz Angel of Death. Stroessner ruled with an iron hand from 1954 until his overthrow in 1989. His loathing for the indigenous was a homegrown version of the genocidal German actions in Namibia.

excellent work and research. Fine words, sir!

It's sad to consider that primate history has been a cycle of erasure from the early hominids to the tribal era in which we live. Periods of coexistence seem to be the exception rather than a fundamental norm. Thanks for re-telling the Ayoreo's story. One of the unfortunate many in our history and pre-history.