Jersey Island Gothic

I do not blame you, Maharaja, for hitting an innocent man. For cruelty comes quick to the powerful. — The Mahabharata

This is a 1753 map of the Channel Islands, an archipelago located between the south coast of England and Normandy. At the bottom is Jersey, the subject of our inquiry.

Jersey’s history is curious. It was the home of Victor Hugo from 1852 to 1855 and it was also the only piece of British land to have been occupied by the Nazis during the Second World War. It is best known nowadays as a notorious off-shore tax haven for insecure dictators and international gun runners, as well as being subject to a criminal investigation into the long history of serious abuse at its orphanages and juvenile detention facilities. The landscape of Jersey is considered quite beautiful. It is verdant and lush, full of winding paths and secret chambers, and the island’s salt sea air is considered healthy and rejuvenating.

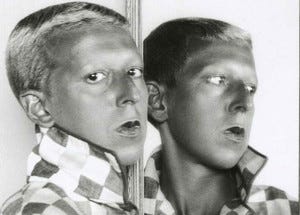

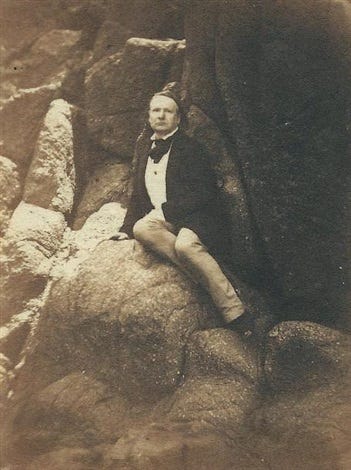

Another reason that Jersey is inclined to mystery is its liminal legal status. Since 1204, the Bailiwick of Jersey has been a self-governing entity, though it is nominally an English Protectorate. Jersey is able to hide an array of colorful characters, many of whom have never set foot on the island but all of which depend on its opaque status as a global hub for financial services. Like all islands, it has a strange relationship of dependency and distinction to the mainland. Islands have always been the abodes of enchantresses, shipwrecked souls and fabulous sovereigns. Jersey generates these myths knowingly. As a safe haven for the wizards and alchemists of worldwide banking, it is a land of boundless freedom from oversight and regulation. Jersey also drew artists, another group known for their self interest and solitary habits. Here is Victor Hugo, photographed right after he landed there, staring seriously from its prehistoric landscape:

Hugo and his household held regular séances in their home. Visited by all manner of famous dead, Hugo assembled a large and strange manuscript of channeled communiqués from the Beyond. This paranormal book has been the subject of controversy, as most literary critics do not accept authorship from the spirit world. It is commonly supposed that Hugo’s wives and daughters wrote most of it. Perhaps, Hugo was certainly the author of these stunning paintings and drawings executed while he lived on Jersey and Guernsey:

Delacroix insisted that had Hugo decided to paint rather than write, he would have outshone any artist of the century. Andre Breton detected a kindred spirit in these mysterious works. Their hermetic symbolism and collaged landscapes seemed similar to the oneiric obsessions of the Surrealists, and Hugo likewise incorporated cigarette ashes, cut-outs and everyday junk as elements in his works. There is a fine book of his artwork called Shadows of a Hand, which may convince you that Delacroix was right.

An earlier exile on Jersey was Roger le Breton, one of the four men who assassinated Thomas á Beckett in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170. Their motive was revenge. Beckett had refused to allow William X, Count of Poitou, to marry his beloved and the Count subsequently died of a broken heart. The following grisly description of the death of Saint Thomas á Beckett has come down to us. The comparison of flowers to blood and gore purpling the Church stones has a touch of true Surrealist cruelty:

But the third knight inflicted a grave wound on the fallen one; with this blow he shattered the sword on the stone and his crown, which was large, separated from his head so that the blood turned white from the brain yet no less did the brain turn red from the blood; it purpled the appearance of the church with the colors of the lily and the rose, the colors of the Virgin and Mother and the life and death of the confessor and martyr...

Foliage borders this piece of incunabula depicting Beckett arguing with Henry II. Henry’s descendants are listed below in linked hoops, forming what looks like a Kabbalistic tree of the Royal bloodline, accursed for the crime of murdering the Archbishop (a martyrdom which also made him a Saint). Jersey is obsessed with flowers and trees, as we will see. Also with curses and secrets and intrusions into the blood.

Lillie Langtry was a descendent of Roger le Breton. Actress, socialite and muse, she was one of the most famous celebrities of the Edwardian era:

At the top of her admirers was Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII and Emperor of India. She would also have affairs—and the occasional child—with the Earl of Shrewsbury and Prince Louis of Battenberg. Encouraged by her close friend Oscar Wilde, she became an actress. When she moved to the United States, a town was named after her, as well as the notorious saloon/ courtroom of another famous friend, Judge Roy Bean. She died in Monte Carlo in 1929.

The famous Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir John Everett Millais was one of many artists who painted her portrait. Like Lillie, Millais was a Jersey native. Millais is best known for this painting of drowned Ophelia:

In his portrait of Lillie Langtry, she holds a flower:

It is an Amaryllis Belladonna. The painting caused a stir when exhibited at the Royal Academy and gave Miss Langtry the nickname of The Jersey Lily.

The flower’s name derives from Greek legend: a young girl falls in love with a conceited shepherd. If she can create a flower out of nothing, the shepherd says, he will love her in return. She stabs herself in the heart and the spurting blood of the wound then forms a crimson flower.

There is other lore around the Amaryllis Belladonna. A medieval legend tells that when a suitable husband was being found for the Virgin Mary, Joseph stepped forth and an Amaryllis sprouted from his walking stick.

The Amaryllis is a native of Southern Africa and was brought to Europe on board the great slave ships. It became a popular ornament on plantations. Pink lilies lined the hedges and roads leading to the great manor houses. Out in the fields, Blacks were worked to death while these beautiful flowers nodded in the wind.

The Amaryllis is part of the nightshade family. The most famous daughter of this line is Atropa Belladonna, or Deadly Nightshade, which is an aphrodisiac or a poison, depending on the dose. Its first name refers to the three Fates who weave destinies and it is a perennial favorite of witches.

Here is a photo of the Battle of the Flowers parade, an annual fête celebrated on Jersey since 1902.

It is held to commemorate the coronation of Edward VII, former boyfriend of Lillie Langtry. When day ends, a floral Viking ship is pulled through the Island’s streets for the so-called Moonlight Parade.

The Battle of the Flowers is really the Lughnasa, or harvest festival, which takes place on August 1st (the parade date has been moved to the second Thursday of the month). This feast of first fruits is called Lammas in England; modern Gaelic is Lunastal; Old Irish, Lughnasadh. An old saying goes, “Summer’s over: today is Lughna Day, the night stretches.”

The synchronizing of the festival with an old folk-custom of pre-Christian origin joins the king to the season and the crop cycle. Even the name, a foliate war, evokes the Cad Coddeu, The Battle of the Trees, a Welsh pagan epic which conceals a sacred alphabet in its riddles according to Robert Graves in The White Goddess. JG Frazer’s Golden Bough notes of that two festivals have always sufficed for kings: one for crowning, the other for sacrifice.

Here is a photograph of German soldiers walking down a high street in Jersey during the Occupation of the Channel Islands, which lasted from 1940 to 1945. The helmeted bobby at the left makes the picture look like a still from an alternative history film where the Axis Powers have won the war.

Here is a photograph from the British Occupation of Kenya, mid 1950s:

Compare the two. The stream of Kenyan prisoners has switched places with the storm troopers. In place of the cop and the onlookers, we have Kenyan Quislings dressed in a bizarre garb which resembles a cross between Panto highwaymen and madhouse Napoleon impersonators. The composition of the two shots is strangely similar; theirdiff erences only make them more differently alike. For example, the cop and the collaborator look in opposite directions in each picture (for shame?). In place of the verdant Jersey boulevard, there is desert in Kenya. In place of arrogant parading whites, captured Blacks in the second. In place of occupied English in one, the preoccupations of the occupying English in the other.

As part of the war effort, the Nazis built a large underground hospital complex on Jersey, staffed with forced labor from Spain and Morocco. The tunnels are still there, a firm artery in the island’s subterranean mysteries. But perhaps Jersey circulates its own legends—especially the worst ones. There, under the seductive camouflage of fascism and occult powers, lies the dull truth of PO Boxes for shell companies, tedious transactions in board rooms, high-speed wire transfers, and military men in Armani. Names on the ferry schedule conceal themselves under old stories of ghostly craft. Premonitions hide the fantastical wealth passing through Jersey, which like all migrants and travelers never stays too long, taking on new identities in split-seconds, glittering for a moment and then vanishing on the server. This is the real Pit. The old tunnels are a distraction. In the end there is nothing in them but rust and broken plans.

More than 2000 British subjects were deported from the Channel Islands to Germany. Among these were at least seventeen Jews, who were subsequently murdered at Auschwitz. The rest ended up in forced labor camps, where they survived or didn’t. Nearby Alderley Island was turned into a concentration camp for both Russian POWs and anti-fascist partisans from the Spanish Civil War. The ancients of the Channels considered Alderley an isle of the dead. In some places, it is still believed that fishermen hear a voice in the night which tells them to ready their boats. Weighted with spirits, these little craft cross over to Alderley shore.

The Germans were ferrymen, too. While their cargo could expect to endure typically harsh treatment on Alderley, the natives of Jersey were able to enjoy the cinema:

By the end of the war, Jersey could boast of a large number of inhabitants born with German blood. The Deaths’ head was the grin of unwedded nights, a secret scene in the wood or warm fleeting moments in those chilly tunnels. It is hard to recount this fact and not sound like some old puritan—even if love was found among the SS. Islands have always been the place where the mysteries of love are explored. Gods are made on islands, gifted to swans willing and unwilling. And there is always some horde hidden in a tree, a fleece or an indestructible sword—another prize for the intrepid lover who washes up on desolate sands.

The Surrealist Claude Cahun, née Lucy Schwob, managed to resist the charms of the Third Reich. Ms. Cahun and her life-long partner Marcel Moore settled on Jersey in 1937. In Paris, they had counted artists like Andre Breton, Henri Michaux, and George Bataille as personal friends. They were fixtures at the famous Shakespeare and Company bookstore, where they would sit and listen to James Joyce read from his books. They participated in many of the early Surrealist exhibitions, contributing photography, essays, and pamphlet art. Note the object between Ms. Cahun’s teeth in the photograph below. It is the emblem of the eagle holding the swastika, common to the breast pockets of Nazi uniforms.

Claude Cahun was the niece of the great fin de siècle writer Marcel Schwob, whose work was much admired by that famous friend of the Jersey Lilly, Oscar Wilde. Wilde dedicated a long poem to Schwob and Alfred Jarry’s classic play, Ubu Roi, is also dedicated to uncle Marcel.

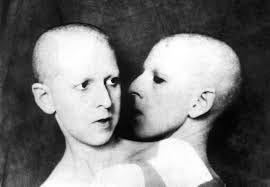

Claude and her partner were offered a chance to flee after the Occupation, but elected to stay in order to plague the new German masters. Here is a picture of them both, a striking example of their photographic work:

It is a disquieting image because both faces seem to mirror each other, yet the reflection is awry, as if one of the images refused to obey the other completely (mirrors crop up constantly in their work, as does the act of trading places). They also eerily resemble the inhabitants of the Nazi concentration camps (the picture was taken long before those horrific images were made widely available), and also perhaps the vampire of the film Nosferatu. The faces are ambiguously male and female, like the first androgynous creations of pagan legend, mannequins staring fatally from out of time.

On Jersey, the two comprised the lions’ share of the anti-fascist resistance. Their love of dressing up, of all the kinds of visual deceit and play so beloved by the Surrealists, was put to good use in effectively convincing the paranoid Occupation authorities that there was a large partisan movement of hundreds of members lurking under the apparent compliance of the island citizenry. Blasphemous leaflets appeared, threatening death and mayhem and targeted assassination. Other pamphlets were written as if they were the confessions of a disillusioned German soldier, prophetically warning of an impending Allied victory. Some of these had been slipped surreptitiously into soldier’s pockets or put into the cars of high ranking officers. Until they were finally caught, their outward eccentricity—they dressed in outrageous clothes and lived next to a cemetery—had actually shielded them from scrutiny. They seemed harmless spinsters, right in line with the island’s dopey Spiritualists and mediums. At the end of the war, the two were sentenced to death by Jersey’s version of Vichy, though the sentence was never carried out. While in jail, they amused themselves by stealing the toilet paper out of the guards’ bathroom in order to write letters to one another.

Here is another of their photographs, a living menhir, showing perhaps that the ancient stones, unlike the Jersey Bailiff, resisted the Nazi yoke:

Below is a photo of La Hougue Bie, a long underground passage covered by a great barrow. This Neolithic ritual site was later converted into a church (you can see the cross on top of the stone structure at the head). The Nazis used it as a lookout tower during the Occupation. Sacral sunlight passes perfectly though the shafts at the dawn hour of both the spring and the autumnal equinoxes. Like Stonehenge, the building is the work of an ancient, pre-Druid cult. Their cosmology is walled off from us in time, but some people believe that they have cracked the code. The problem with recognizing the signs of codes and secrets is that these very codes camouflage themselves. They are nearly impregnable, which only compels the arrogant to lose their way in a labyrinth that does not truly exist. Perhaps everything was transparent when these structures were made, a clarity which is no longer possible for various social and historical reasons. All that remains now is the overwhelming conviction that we stand before a vast maze, the last remnant of a crystalline way of seeing the world whose wreckage appears to us like some inscrutable cypher.

Jersey Island is a place of caverns. Caverns and caves in religion, in the island’s topography, in the grottos and hideaways of its finances. Nothing on Jersey is capable of telling the truth. Jersey is a frozen asset. Like art, it relies on lies.

Along with the notorious Cayman Islands, Jersey is one of the world’ most desirable tax havens for the ultra-rich of all stripes. 53% of the island’s economy comes from the bankers, lawyers, and accountants who mind this tremendous cache like Nibelungen guarding gold.

This is Sani Abacha, the former dictator of Nigeria:

Some, if not all, of the $3 billion Abacha pilfered from Nigerian coffers ended up safe and secure in Jersey banks. When not engaged in kleptomaniac pursuits, Abacha kept busy by putting his opponents to death. Nigerian petrodollars ensured that the West recognized his regime and that Nigerians remained in abject poverty under the thumb of a glitzy thug with a yen for chesty medals. Epaulets, gilt-embroidered cap… along with dark sunglasses, this was the international style of autocrats and Junta. The look is rather passé by now and their brand of primitive accumulation is distinctly old school, though it is by no means extinct, and Jersey respects both atavism and hypermodernity.

The man above with the toy is another Jersey client, Sir Dick Evens, chairman of BEA Systems, a powerful Anglo defense contractor. In 2008, his firm was the largest in the business. BAE’s clients have included General Augusto Pinochet and the governments of Indonesia, Zimbabwe and Israel, as well as the US and the UK. It has been indirectly involved in the production of nuclear weapons and, until recently, it manufactured cluster bombs.

It was apparently Sir Dick’s ability to swallow sheep’s eyeballs at lavish Saudi banquets that enabled him to score the biggest arms deal in British history—a cool ₤43 billion in the mid-1980s. BAE later pleaded to guilty to charges of bribing Saudi officials, managing ghostly Swiss bank accounts, money laundering, and operating slush funds through front companies to facilitate bribes. BAE and its lobbyists, together with the Saudi royals—who promised terrorist attacks on England if vital intelligence was withheld by their state intelligence services—forced Attorney General Lord Goldsmith to halt the Crown’s inquiry. There was also considerable pressure from major British political figures such as Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. However, the investigation was then picked up by the US Department of Justice, who finally issued an indictment. This greatly embarrassed the British Ministry of Justice, showing them to be a rubber stamp for international arms dealers and their ruthless clients.

Everything that passes through Jersey’s high tide washes up clean and anonymous, transformed by a nearly divine providence which bestows nobility of purpose on war criminals and moral conviction on mercenaries. Old gods permeate Jersey. One of BAE’s parallel entities, created in order to make ‘sensitive’ payments, was named Poseidon. There are other mythical creatures on the island: mermaids, who come up with rare pearls; the Morrigu, who wash the blood from the clothes of warriors; the Sirens, who call roving merchants to wreck on deceptive shores.

Recently, the newspapers were full of stories about Jersey’s youth homes and juvenile detention centers. These institutions were apparently the locus of an organized system of horrific child abuse spanning decades. Skeletal remains were found in underground chambers (which later turned out to be either centuries old or, inexplicably, coconuts). High-level members of the Jersey government were implicated in covering up awful crimes or directly participating in them. Members of the island’s youth services came forward with damning testimony and the victims, most now in middle age, recounted tales of abject cruelty and suicide. British television was flooded with images of police excavating basement floors and poker-faced detectives glaring at nosey cameras. Here is Jimmy Saville visiting the Haut de la Garenne home in the 1970s, surrounded by starstruck children while a proud matron looks on:

But the revelations of a vile and secret cabal of the devotees of excess a la Sade’s Friends of Crime only served to mask the ordinary depravations of such places. Under the regimen of administered days, wards of the state are the subjects of a system of severity that is infinitely practical in its brutality. When the secret worldwide coven of torturers was revealed to be a chimera, the schools continued on their business—just like the rest of the island. Celebrations of flesh and torment have amateur as well as professional devotees. Anonymity is general on Jersey. High or low, it is considered to be a singular island virtue.

Jersey has a formidable history of witch hunting, especially considering its small size. From 1562 to 1736, a fever of show trials and witch-burning swept the island. The Mather family, of whom Judge Cotton is the most famous scion, emigrated from Jersey to Salem, Massachusetts, where they continued combatting the Devil. Jersey historian G. R. Balleine wrote a famous paper on local witchcraft. While he derided the cruelty of the judges, he accepted that a global conspiracy of anarchic witchcraft had actually existed. But he was describing his own time without knowing it—1939, time of fires, time of a magical ideology and its dark inverse symbols, time of shapeshifting identities and the muddy erasure of names. Bewitched night, night of crystals, young inscrutable years projected onto the necks of lilies. Beware the insidious column and the Protocols. Invest in Jersey.

Edward Paisnel may also have visited the most notorious of the care homes, Haut de la Garenne. Paisnel was another famous native of Jersey. His wife wrote a biography of him:

Between 1957 and 1971, a series of horrific attacks on women and children plagued the island. Suspicion fell on Alphonse le Gastelois, a quiet, hermetic man prone to taking long walks alone in the country. “I love nature”, he said, “I listen to the sounds of the dark and silence.” These crimes were actually the work of Edward Paisnel, a respected businessman and prominent member of the community. In addition to believing that he was a descendent of the infamous mass killer Gilles de Rais, Paisnel built an altar to Satan in his basement and, on his predatory night rides, wore a grotesque rubber mask and a leather raincoat studded with nails.

Alphonse Le Gastelois was stoned and spat upon and finally, after his cottage was burnt to the ground, forced to flee Jersey in fear of his life. He moved to tiny Le Ecrehous Island, seven miles offshore, where he lived as the sole inhabitant and self-declared monarch. Of course the crimes did not stop after he left Jersey. They stopped when Paisnel ran a red light and police found torture implements and his monster outfit stuffed in the back of the trunk.

Here is a photograph of Alphonse le Gastelois:

Fourteen years later, the courts proposed to award him £20,000 and issued an official apology. ‘Jersey crucified me’, he said. He did finally return though, occupying a single room in extreme poverty, rent generously paid by the Bailiwick in lieu of the court money which never arrived, until he was moved into a nursing home where he died in 2012. There have been numerous plays and films based on the life and trials of the scapegoat King of Les Écréhous.

The island was more than hospitable to the Third Reich, but it hounded and despised this quiet man who listened to the trees. Perhaps he saw things similar to those that Hugo had depicted in his paintings. Life and the natural world must have seemed overfull to such a person. This vision of abundance is met with incomprehension and hostility on the part of a certain class, which never balks at the greatest violence to safeguard what it believes to be its good name.

Postscriptum:

In July 2009, there were several UFO sightings on Jersey over the seaside town of Gorey. Extraterrestrials seem to hover over troubled areas on earth, though Jersey, for once, is very late in the game. Of all the deities, the Trickster God is the most attentive to humanity. Here, he offers a footnote in the shape of a flying saucer to complete the story of Jersey Island—if only to assure us that nothing absurd has been left out.

![Victor Hugo, Ecce Lex (Le pendu) (Ecce Lex [hanged man]), 1854. Brown ink, brown and black wash, graphite, charcoal, and white gouache on paper. 20 × 13 3/4 in. (50.8 × 34.9 cm). Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris / Guernesey. MVHP.D.967 © Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris / Guernesey / Roger-Viollet Victor Hugo, Ecce Lex (Le pendu) (Ecce Lex [hanged man]), 1854. Brown ink, brown and black wash, graphite, charcoal, and white gouache on paper. 20 × 13 3/4 in. (50.8 × 34.9 cm). Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris / Guernesey. MVHP.D.967 © Maisons de Victor Hugo, Paris / Guernesey / Roger-Viollet](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!U4T8!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd0ba385a-6ca9-46fd-b86c-06c597c88c2b_1032x1500.jpeg)