The right hand lets sand slip through/ All transformations are possible. – Paul Eluard.

Gaze upon the Temple of Dendur, commissioned by Emperor Augustus and consecrated to the goddess Isis on the west bank of the Nile, c. 23 BCE. Today it stands far from Nubia, reconstituted in a famous museum in New York. Nasser managed to get UNESCO to help him sell it to the Met during the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1963. In the end, he got some $16 million out of the US government for further architectural preservation—that is, as a bribe to stop the potential loss of antiquities under the waters of Lake Nasser, the reservoir resulting from the massive Aswan project. Considering what hordes the British Museum looted from Egypt and the Levant, we shouldn’t be too hard on the president. Why shouldn’t an Egyptian get something out of Egypt?

In 1972, the temple was placed in the Sackler Wing of the Met. The Sackler Family has been much in the news recently. As owners of Pedue Pharma, they are accused of having manufactured the American opioid crisis. For the Sacklers, the crisis remains financial. Perdue has declared bankruptcy. The family must surely be in dire straits too, for their attorneys have requested that their personal assets be protected against seizure[1]. In a rare case of judicial integrity, this obscene motion was initially denied. It was then accepted by the US Court of Appeals. The Supreme Court has put the block on hold and is currently reviewing the case.

The lesson is that it is not the crime of flooding the nation with cheap highly addictive drugs that is important, but the definition of bankruptcy. According to U.S. Circuit Judge Eunice C. Lee, “because of these defining characteristics, total satisfaction of all that is owed—whether in money or in justice—rarely occurs.” Tough luck, dope fiends. You see, it’s complicated.

Back in 1952, the same year Nasser’s Free Officers overthrew King Farouk, Arthur Sackler—psychiatrist, marketing guru, art collector, philanthropist—purchased the tiny Perdue-Frederick Company. It manufactured things like earwax remover, but it also made a product called MS Contin. This was a morphine pill used for chronic pain management, equipped with an added time-release property which meant that you didn’t have to take incremental doses. In the early 1990s, Perdue modified the semi-synthetic compound, giving it one and a half times more power and renaming it OxyContin. Contin stands for continuous. It continues to be popular.

In 1967, the cost to transport and house the Temple of Dendur was put at $3.5 million. Patriarch Arthur Sackler offered to underwrite it. The Sacklers got a wing with their name and the public could marvel at a late-period Egyptian masterpiece. They probably marveled twice, as New York citizens ended up paying a third of the cost after Arthur reneged on the original deal.

The prominent silver letters on the Met gallery and other institutions around the world stand in marked contrast to the greatest of the Sacklers’ contributions. For years, one had to dig deep to find the Sackler name in connection to Perdue Pharma. Their names didn’t appear on official websites and they delt with corperate affairs with great internal tact. Philanthropy is seldom so humble.

But the warmth of Oxy has its source in glacial springs, flowing out with the stroke of a pen along highways and tracks, human and concrete, born from the maneuvers of Perdue’s advertising and influencing machine. This timeline of the drug’s metamorphoses and Perdue’s confidential memoranda shows minds of rare ruthlessness at work. Studies were paid for and faked, information suppressed, critics neutralized. The Sacklers and their attack dogs behaved like yuppie Whitey Bolgers, with similar swagger but less heart. Yet sometimes they were clear and to the point. Future CEO Friedman: “Our current MS Contin business has created a ‘franchise’ with certain physicians who routinely write prescriptions for the drug…” Physicians and GPs “may be the bridge that we can use to expand the use of OxyContin beyond cancer patients to chronic non-malignant pain.” By bribe or trickery, doctors will be made suckers for the narcotrafficking octopus called Perdue. Every door exists to be opened. Under the viaduct, tents can be opened too. Let’s be straight: the drug does work. Limbs tingle, agonies subside, you are able to sleep again. First you dream, then you die.

The British Museum has removed the names of Raymond and Beverly Sackler, but their specters still appear in electric memories. After acknowledging the generous past support of this nest of vipers, a Museum spokesman announced that ‘a new era’ would begin without Sackler largesse. A joint statement states cryptically that “the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Foundation and the British Museum have worked together for over 30 years and, as early development work begins on the Museum’s new masterplan both partners believe it’s a timely opportunity to take this step.” Though the document admits that the Museum accepted Sackler funds “between the 1990s and 2013”, it keeps the figure discreet. The trick is to keep the better part of valor vague and cloak the indefensible with dizzy optimism.

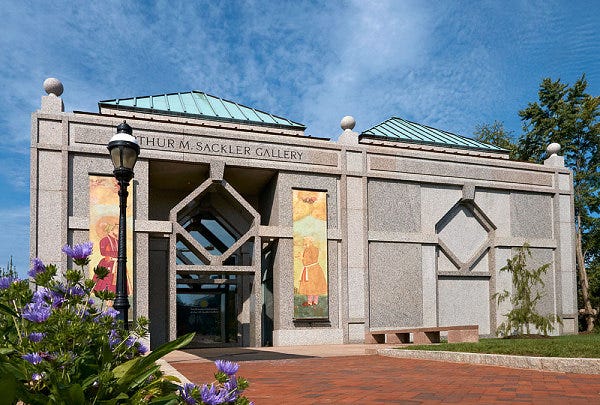

There are loyal holdouts. In addition to its repellent obsession with Native bodysnatching and sacrilege, the Smithsonian still proudly displays the Sackler name on high. The building named after Arthur looks like a gaudy pet mausoleum. One of its exhibits celebrates ancient Yemen, perhaps because we have helped Saudi Arabia destroy the current property. But it is refreshing to see that the Smithsonian does not deal in shame and remains stubbornly oblivious to a name most people equate with Nazi doctors and serial killers. Other parties have bowed and scraped and pried off the offending letters. The American Museum for Natural History once boasted a Sackler Institute for Comparative Genetics and a Sackler Educational Lab. The Tate Modern was distinguished by not only naming rooms after the Sacklers, but also escalators. The Guggenheim’s Sackler Center for Arts Education finally went last year. Tufts University made 2019 the Year of the Expunged Sacklers. It must have taken a lot of custodial overtime to remove the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, the Arthur M. Sackler Center for Medical Education, the Sackler Laboratory for the Convergence of Biomedical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, the Sackler Families Fund for Collaborative Cancer Biology Research, and the Richard S. Sackler, M.D. Endowed Research Fund. The Louve was lucky enough to have a rule in place restricting room names to a 20-year lifespan, Sackler being up this year anyway. Most of the major institutions in England seem to have Sackler stamped somewhere on them. Most have been peeled off, but Westminster Abbey still has Sackler windows and Cambridge keeps a couple dreary lecture halls. You can no longer panhandle for dope money by the Sackler Crossing in Kew Gardens because it’s called something else.

As for the resurrection process, it is quite simple: the Sacklers agree to have their name removed. The institution then gushes over their nobility. Past gifts remain past gifts. The future is clean.

Shooting up Oxy allowed you to bypass the time-release mechanism and get the full payload in one go. Under pressure in 2010, Perdue finally added a polymer coat to make the drug very hard to mainline or snort. Medellin stepped in. Market logic dictated that dealers were able to offer a tried-and-true alternative: heroin. A partnership of mutual interests had formed, as Medellín branched out from cocaine to heroin in North America. A comparison between the founders of the two corporations is instructive. Unlike the Sackler brothers, lay collectors of art and endowers of chairs and departments in a few rich universities, Pablo Escobar built hospitals, clinics, schools, housing complexes, and parks in the poorest districts of Columbia. His murder in 1993 was followed by an outpouring of national grief from those who owed their education, homes, health, and jobs solely to El Patron.

Room 34 of London’s National Gallery was once the Sackler Room. It houses works by Constable, Gainsborough, Turner, Reynolds. One of the paintings in the room is “An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump”, a 1768 oil by Joseph Wright of Derby. It depicts an experiment: the air in a glass chamber is sucked out in order to suffocate a grey cockerel. Debate on whether the painting is anti-vivisection usually revolves around psychologically interpreting the faces of the onlookers. The women in the picture are all horrified in varying degrees. The men do not doubt the necessity of cruelty to resolve certain scientific questions, and they mostly stare dead ahead, fixed like an august board of directors or the audience of some hypnotic song. At the time, the cockerel was a very rare bird in England, making it a strange choice to use as a test subject.

No one considers the Sacklers innocent. But neither are they guilty, despite the pleas and legal convictions. They exist in an intermediate zone, stained by association and richer for it. The poor are guilty before they are even charged. Justice uses a universal language, but the exact same meaning in the Law changes depending on who is able to answer. We must admit our guilt in court, and so we travel through a parallel system. The Sacklers have a third option—they can pay, paying blamelessly and sacrificing only an innocence no one can define. The answer of the Sacklers comes from the fleet of experts under their retainer. This answer allows for contradictions, contradictions that are identical to those which deny others parole. As for the final sentence, the extension of the parallel decides. When the Supreme Court issues its judgement—the outcome of an eerie séance with the realm of the juridical dead—this decision will reflect either the eccentricities of an unelected body or the will of the privatized State. Like dreams, the Law is interpreted according to itself.

What did the anonymous dreams of Corey Juaire and Joe Scarpone tell? Dreams of the vultures adorning the Sacklers’ gift of an ancient shrine, birds of prey over the dark hills of Kentucky and Ohio? In a virtual public hearing in March of last year, the Sacklers were forced to listen to the questions and curses of the mothers of these dead men. Or they were at least present in some disembodied way. They offered no reply. How could they? There is no common language between the two groups—not English or Latin or nothing. Hadn’t Perdue’s lawyers already blamed the addicted and the overdosed, lecturing graveyards and waste spaces about ‘personal responsibility’? Such responsibility does not exist for the gods, however. Osiris lay with his sister Isis. With blank faces and implacable calm, Richard and Dame Theresa Sackler may have caught a word or two from the computer screen before they went off to sleep undisturbed.

Sins are passed down, weighing heavier on those not named Sackler. Birth defects arise from parents’ addiction to Oxy. Though the Sacklers have given no real public statement, the words of the philosopher Harry Lime might sum up their worldview: “Look down there. Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving — forever? If I offered you twenty thousand for every dot that stops, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spare?”

Farther down the bloodline tree, some members of the family appear contrite. Their weak guilt makes this contrition merely cloying. In comparison, the silence of the head Sacklers at least shows a realpolitik which suits the crime. One day the guilt-ridden relations will sleep well too. The $6 billion settlement is perhaps for their benefit. No one really expects them to give up everything for those who lost what little they ever had.

If the shining family name has vanished on most of the major institution doors, the money is still congealed in the commodity, art or opioid, hanging on walls or scraping at the central nervous system. And offshore, too—where even more fabulous family heirlooms lie behind blind trusts, shell companies, and straw holders. The ancients buried riches along with their mummies to pay the ferryman and secure real estate in the Afterlife. Each day, ram-headed and withered Ra is transformed into a youth with the new dawning sun. At least that is how the dream goes, according to the makers of the dream.

Note: Most of the information above is from the superb reporting of Patrick Radden Keefe, author of the definitive work on the subject, ‘Empire of Pain’.

[1] In 2007, Perdue’s president and top lawyer pleaded guilty, were fined $34.5 million and got probation. So the sop here is that Perdue will pay $6 billion in return for future legal immunity.