“The informer had never, could never have, believed that the law was definitely codified and the same for all; for him between rich and poor, between wise and ignorant, stood the guardians of the law who only used the strong arm on the poor; the rich they protected and defended. It was like a barbed wire entanglement, a wall… The informer asked only to find a hole in the wall, a gap in the barbed wire…Once over the wall the law would no longer hold terrors. How wonderful it would be to look back on those still behind the wall, behind the barbed wire.” - Leonardo Sciascia

With the arrest of one Rex Heuermann, the Suffolk County DA claims to have conclusively solved a series of murders spanning from 1996 to 2011. The Long Island Serial Killer, AKA, the Gilgo Beach Serial Killer, may have been responsible for eighteen deaths or more. Here we encounter the first mysterious question: How many? Which is quintessentially American contemporary, whereas Whodunit, despite its old hardboiled ring, sounds pretty Victorian these days.

The killings dovetail with several others, maybe even several other killers, including a nasty little piece of work named Joel Rifkin, who haunted roughly the same area and liked to deposit severed heads on golf courses. Is this an off-handed insult to the Hamptons set? Did he also consider leaving limbs in vats of Nassau wine? Killing the poor and displaying them to the rich may seem like a joke, but I see it as more of an amateur’s attempt to ingratiate himself with the pros.

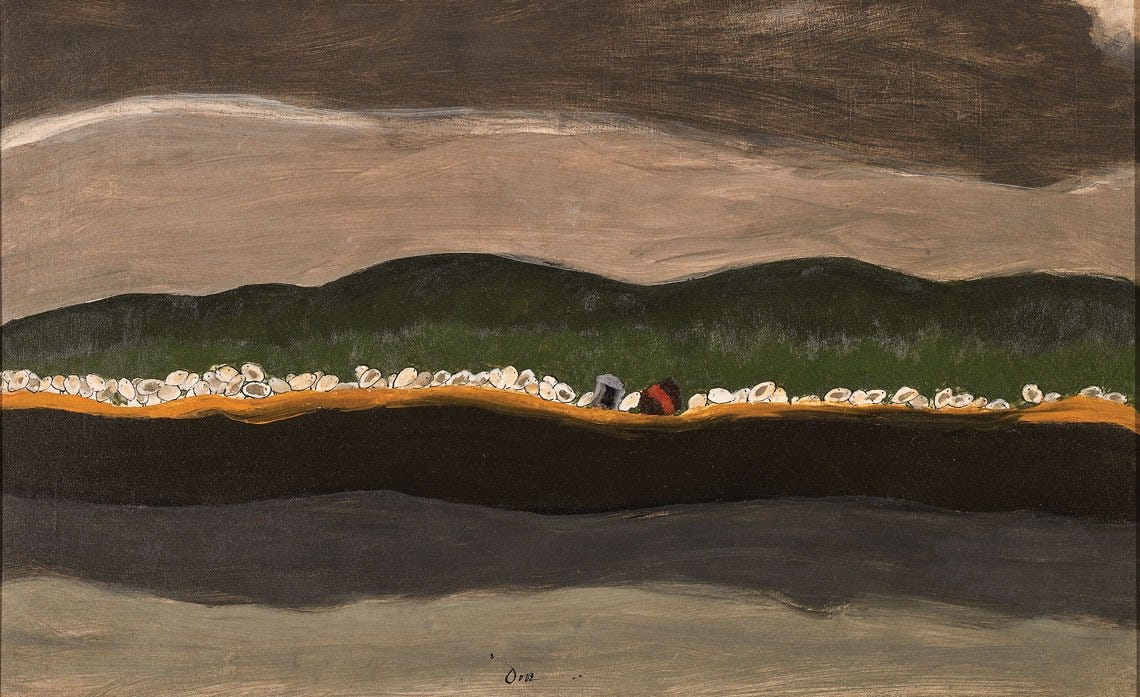

The lonely stretch of Long Island where the ladies were murdered looks as if it were cultivated for just that purpose. Remote and marshy, colors of sand and mud, rusted pikes sticking out here and there like broken teeth. A topography of the dead, dark ryegrass fields hiding soft remains; landscape and body merging, the body of work of the killer and those bodies who work (prostitutes), names in small type next to disused waterworks and waste spaces off Ocean Parkway. A human terrain.

It also brings to mind the icy paintings of Andrew Wyeth. Everything is brittle and burnt over, damp and dry at the same bone white time. In media coverage, the Long Island landscape is usually accompanied by ominous piano tinkling in a cheap attempt at setting a sinister mood. The point is to make you imagine that you are driving alone at night in the rain, passing by areas of potential interest as killer or detective. Either way you are a part of the American mythos of a personal quest via redemptive violence. A tourist in your own mind, you can watch yourself become a fleeting image in the rearview mirror. Through the miracle of electromagnetic wires, you can finally be in several places at the same time.

If the killings were done in strict darkness, their discovery is in the bright counterfeit of on-camera daylight. Men and dogs slowly move through the frame, combing the underbrush. They look bored, another product of the essentially boring universe of serial killers. For the murderer, there is tedium of hiding the evidence, coming up with an alibi, teasing the victim’s family and searching the web for clues to your own whereabouts on the nights in question. It is as if the whole thing was just going through the motions. But the rules of the game have been respected, everyone is happy and all is where it should be. Reporters and analysts can sleep the sleep of the just. So can the cops, the DA and the good people of Oak Beach and Massapequa Park. Perhaps Heuermann himself is sleeping justly in his cell, for we cannot discount that he really wanted to be caught. Even he is granted justice in the end, because as we know and cherish and do endlessly repeat—justice is for all.

Question: Why didn’t the Suffolk County police just fit up someone up for the crimes? Absence of interest, outside pressure? There was no lack of suspects or potential suspects. Like crime, false conviction is eccentric and bound by provincial ways of doing things, or by quota, by other unholy entities.

Question: Does no one find it strange that none of the reporters’ daughters, wives, sisters are prostitutes? Distance is one thing, remoteness is another. What is it about everyday life that so unnerves them? They don’t know.

In newspapers and on TV, the biographies of the dead are recited with an irritating pang in the voice, that cloying reflex which says pity. Words like ‘uneducated’, ‘unfortunate’, ‘troubled’, ‘substance abuse’ (the latter was once used only for the rich), and ‘broken home’ are trotted out like fairy tales and destinies. The police are more honest when they state outright that whoring is dangerous work and death is just one hazard in an ancient trade. Others say ‘sex work’, but in their heart of hearts, they do not consider it work or sex. Voices quaver, serious looks, details of social service calls and absent mothers, drunk fathers and dope and pimps and penury. Nowhere is any kind of joy mentioned, except by the grieving parties who seem to know that everyone out there looks down on them. Their ordinary words are the only extraordinary ones, given without lilt or pregnant pause, stories of birthday parties and a love of poetry and working to get through High School. Nowhere else is there any conviction that everyday life, addled or cracked or busy or chaotic, is ever worth it.

For the dead women, every moment is underscored by some titillating cruelty. And the whole thing, from the killer to his capture is repulsive, banal, overdone… Media also invents lives for the victims, traumatic doubles for reality who ‘slip through the cracks’—never mind that the cracks cover an obscene country, that lone killers are a perfectly logical outcome of this country. The absence of the feminine dead has now become a trope. As if saying repeatedly that they are absent makes them present, as if reiterating their humanity makes them human again, as if pointing out the vicious misogyny in all aspects of the so-called case makes any difference at all.

We are in the slow genocide of the working class. The worst aspect of it is not the boasts of killers or the middling cops but the memorialists. The worst of them are the well-intentioned and the biggest crime is what they are trying to protect. No one thinks the lives of these women are anything but tragic and whole lifetimes are commandeered to reflect the tear-stained accounts of tragedies—which is life itself, not tragedy. The political is removed and replaced by the individual isolated story, which is magical thinking under another name. The gods ordained all of this. Which lets you off the hook.

I read that home sales in the Hamptons have declined by twenty percent this year.

There are many documentaries on the killings, a NYT bestseller, several podcasts and much print and digital. Liz Garbus’ 2020 film, Lost Girls, is based on Robert Kolker’s book of the same name. Reed Birney does an admirable Farley Granger turn as Dr. Hackett, a bizarre footnote in the history of the Long Island murders. In the film and in real life, Hackett constantly implicates himself in the crimes. He claims to have treated an injured victim of the killer right before she died and calls her family to tell them about it; he lies to police, says that he runs a charity that doesn’t exist, forces himself on journalists as the spokesman for the gated community wherein the late Shannon Gilbert was slain. But it seems he had nothing to do with the killings. Like the viewers and filmmakers, he too is fascinated. Pushing his way into the frigid orbit around the crimes, he plays the Red Herring to the hilt as if he were acting out a role in a movie.

What is left: faces smiling into cellphones (this will have to do for resurrection, making the victim seem whole because she is documented), or mugshots, my this and that love, lost surveillance footage. And the perpetrator—or supposed perp or one of the perpetrators—stalked and seized by time, sitting sullen, overweight, suspicious by his eyes. We are told that his house was messy and falling apart, which should have been a tip off, right? He was also an architect, which is apparently less foreboding.

Outside of both justice and injustice lie the bodies, excavated and identified, taken out of burlap sacks, teeth and prosthetic limbs examined, then buried twice over.

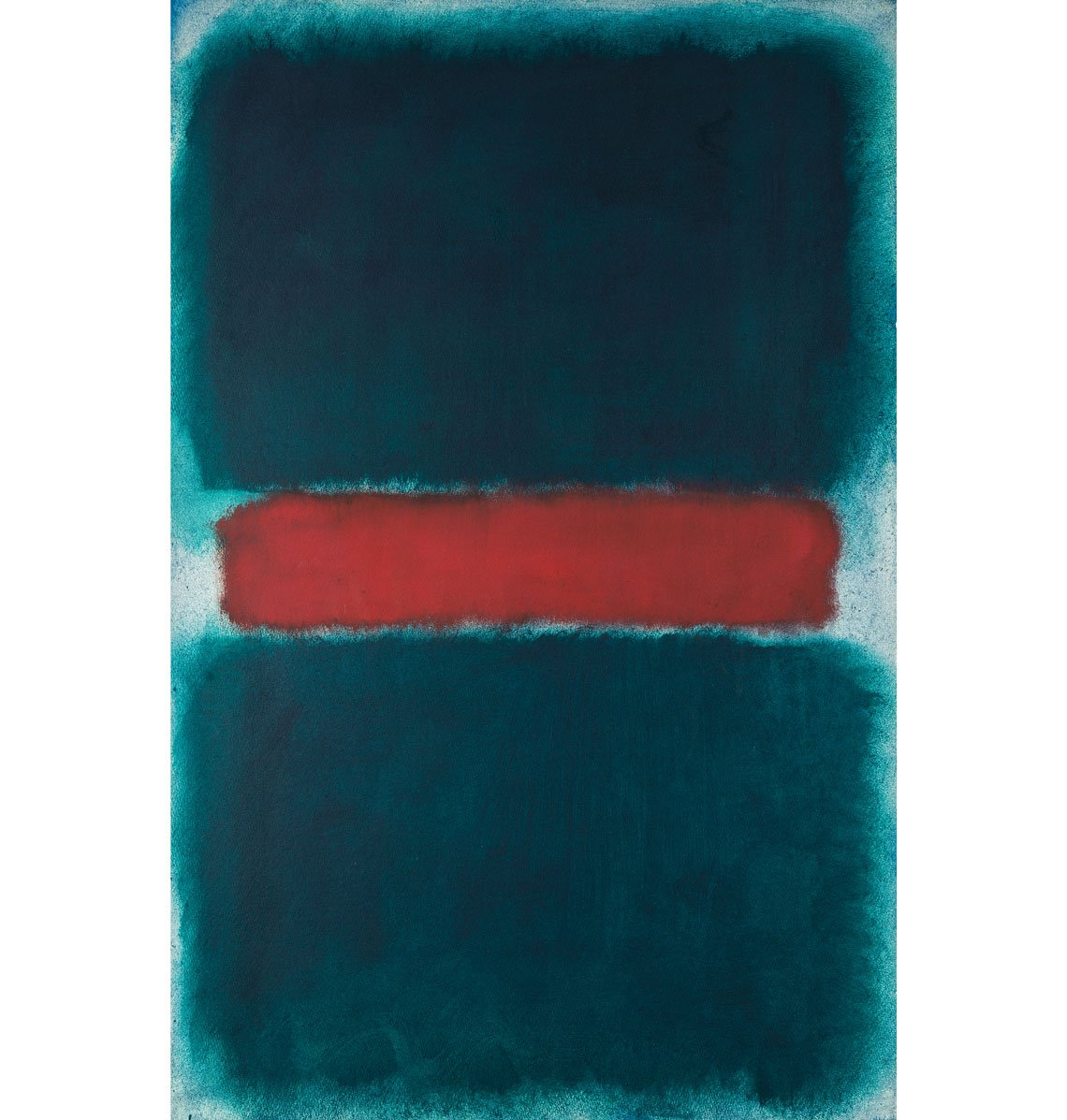

Though connecting art and murder only makes for bad films, Long Island was something of an artists’ retreat during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Some of these paintings appear here, rather than the usual scroll of portraits of killers and victims who stare out at the reader as if they were all martyrs and saints. And maybe the painting below by Mark Rothko, made on Long Island in 1968, is an accurate depiction of its suicidal landscape. Dreary and enervated, devoid of image and joyless, a hollow reflection in a blotched windshield. A smear which subordinates life to abstract expressions—that is, to a purely emotional response which abandons the forms of things in favor of a personal preoccupation with despair—the processes of a legend-making machine about which nothing can really be said but that here is the inevitable end leading up from the past and culminating in total obliteration. The decision that there can be no more painting ever except this thin ruined skein, dull and confessional, bitter and longing, is made by some expert, by some artist to be sure, but also as the market place dictates. Everything must be paid for.

If there can be any recognition of these suspended specters, things that were once women and are still (the dead also have a present), it will not be possible as long as we assume the profound arrogance to speak for the dead. Speaking for the dead shows only one’s own terror at their perceived silence, a silence that is not silent but teeming—for mothers, lovers, friends good and bad. It is an attempt to wrest control of silence and its double via the supreme affronts of mere understanding and knowledge, annexing the space of the dead by filling it up with drivel about closure, grief, trauma, and the marginalized. When this attempt fails, as it always does, it leaves only the confiscated agonies of the terminally empathetic in place of the human presence of the dead. Where then is the awe at these corpses in earth made instant fossils, an awe that is sacrilegious, impersonal and mute? Must there not be something like awe at these prostitutes, at these walkers. And this in the face of the NYT, whose journalist regrets that these women were mostly ‘uneducated’. OK. We’ll take that up. Let us consider another kind of education that is always paid for, the collection of a student debt which never compromises. Then we shall see who is really educated.

Accept that the final truth of a violent world—the indisputably violent world in which we all live—is that of dying alone in a lonely place. This is not much to ask of us for a moment, considering the stakes, and who knows, it might even help us. To have lived all one’s life in the shadow of this truth is to know it without needing to recognize it, even when blind terror obscures the senses and one resists valiantly or resists not at all (the impossible truth of those who willingly follow their executioner is the paradox that maybe it will be better for me if I do, though I know full well that the outcome will be the same). Long Island decides. In this shitty little place, no emissary of hell on her tail but some impotent little bastard, what use is bravery or cowardice or the blackmail of tears? Early dawn closes around and no one imagines anything. Who would not be in awe of one who faced this most primitive of facts—not as some concept drubbed into heads in classrooms, but in the cold clear night of an unrevealed revelation, a revelation that cannot be communicated or learned or taught—the only lesson in the world which demands that its teaching must not be survived?

So what suffocates this initial awe, the first and most profound reaction on our part? What makes things comfortable, what smothers this piercing convulsion by which we are almost allowed, for a split of a split second, to change places with another? The relentlessly grim entertainment called True Crime, seducing almost all of us immediately and without resistance. The poison floods out, whether the outlets are respectable and sober or trashy and terrific. Both the killer and his victims are valorized—that is, made worthy of informational exchange and transformed into bingeable series, imprinted as thrilling nodes whose duty is to make us virtual targets and assassins. And no one doubts that this is a game played for entertainment’s sake whose center cannot be approached but whose bloody fantasies force us to admit that of all the terrible qualities we possess, Evil is probably the least of them.

Artwork, in order of appearance: Arthur G. Dove, Sea Gulls, 1938; Andrew Wyeth, River Valley, 1966; John Frederick Kensett, Eaton’s Neck, Long Island, 1872; William Merritt Chase, The Big Bayberry Bush (The Bayberry Bush), ca. 1895; Sanford Robinson Gifford, Fire Island Beach, 1878; Mark Rothko (1903–1970), Untitled, 1968.

Women, in order of disappearance: Maureen Brainard-Barnes; Melissa Barthelemy; Megan Waterman; Amber Lynn Costello; Jessica Taylor, Valerie Mack; Shannon Gilbert; "Jane Doe No. 3" or "Peaches" and her daughter, “Baby Doe”; "Jane Doe No. 7”, “"Jane Doe No. 6", Tina Elizabeth Foglia; Jacqueline Ashley Smith; Andre Jamal Isaac; Jamie Diane Seymour; Tanya Rush; "Cherries" / Unidentified woman, Mamaroneck; Unidentified woman, Lattingtown.