Now that the Long Island Serial Killer is in custody, the list of suspects in the crimes is free to expand further. Exciting new possibilities include former Police chief James Burke and an unknown woman who may even be his wife, as well several men already imprisoned for earlier murders. Solving the case opens it up to interpretation. Doors that were closed in the faces of the victims and their families stand wide open.

Gutter press like The New York Post is richer than the more sedate media because it has no problem with outright contradiction. Suspects and theories spiral out endlessly; multiple people can be responsible for the same killing; finality awaits revision on a dime. With every DNA sample, the intriguing possibility that this genetic fingerprint could have been left at any time makes the preposterous quite possible. Perhaps she escaped one killer only to meet the next. Perhaps a coincidence implicates one man who is guilty of other killings but not this one…

Another irony: those investigating the murders were also being investigated. Namely, Suffolk County Police Chief Burke, whose refusal to deal with the FBI was initially written off as pure ego. It turns out that his office was also under Federal probe. So was this then the real investigation, the killings a mere excuse to enter the warren of a man who flaunted his abject corruption beyond what is permissible? The case around the murder case was solved comparatively quickly, probably due to official embarrassment.

Comic details rolled out in the indictment: Burke outfitted his office with amenities like a 24-hour bar and had his underlings tail a girlfriend he suspected of infidelity. In 2016, the top cop received 46 months in the federal pen. His comeuppance came via his hobbies and lusts. After a bag full of sex toys and porn was stolen from his SUV, Burke easily tracked down the thief—a local dope fiend who hit the Chief’s car quite by accident—and then beat him senseless while in custody. Later, back in the joint for parole violation but now taking a turn as the star witness against his torturer, the junkie gloats that they’ll ‘both be wearing khaki now’. As for the killings which littered his time in office, Burke isn’t totally in the clear yet. Tabloids and public suspicion keep him around, at least as a complicit party.

Burke owed his career to an earlier infamous crime. After being chief witness in the prosecution of the grotesque 1979 murder of thirteen-year-old John Pius, he shot through the ranks of the department with the patronage of the state’s prosecutor. Despite some eccentricities—getting caught with prostitutes, leaving his gun around absentmindedly—he flourished. His loud and bullish presence made him a popular character, the sort of no-nonsense provincial cop once associated with fury at ‘forced busing’ but now enshrined in the temple of American Folksiness.

For Burke, the pesky investigation into his investigation produced new needs and expediencies. Survival as the first law of public office means managing inquisitive foreigners, bitching mothers and intrusive plants. He did not survive, but not in the same way that Maureen Brainard-Barnes and Amber Lynn Costello did not.

These women were all caught in a Red Harvest situation, pinned between a notoriously unscrupulous police department and a ferocious murderer. The latter was protected by a state office which could be considered a silent partner, refusing to gather evidence, obsessed with covering its own malfeasance, and only discovering the bodies by accident. These parallel forces of quarry and pursuer worked in unison, each providing the other what the other lacked. And conspiracy means precisely that and nothing more: forces that conspire together, no matter their distance, no matter their mutual antagonism, no matter whether they are aware of each other’s very existence or not. In the center of these intersecting lines of force is one woman, then another and then another, left in clearings and by rivulets like missing baggage.

The murdered women all had clients from the police and judiciary. When told by a Gilgo Beach resident, before whose closed door Ms. Shannon Gilbert stood screaming and could not enter, that the police were on their way, Shannon Gilbert only became more hysterical. The cops arrive an hour later. The full tape of her desperate 911 has never been publicly released. When asked about it, an unusually poe-faced Burke says they figured it was just the ravings of some sloshed party girl. “They’re trying to kill me”. What an absolute scream.

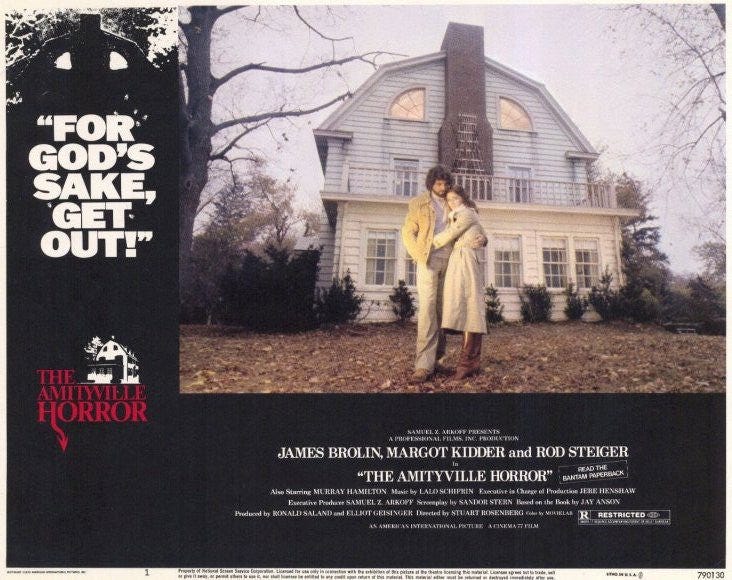

The same year Burke did his star turn on the witness stand, 1979, a big budget junk film made the area famous. Amityville is a village in the town of Babylon, Suffolk County, and thanks to a few murders and a fraudulent ghost claim, it has real staying power in the tat of modern American Gothic (not to mention the mythology of real estate). The massacre in the house at 113 Ocean Avenue, the cause of the supposed haunting chronicled in the books and films, even had mob connections, as if the fact that The Godfather was filmed all over Long Island demanded it. But while The Amityville Horror, ‘based on a true story’, played out on screen and talk shows, someone was killing prostitutes not far from the devil house with glowing eyes.

The Long Island Serial Killer constellation now apparently includes Donald Trump, who hired main suspect Rex Heuermann for “renovation of office space to include minor partition and plumbing changes” at another haunted house, the 40 Wall Street property. Heuermann was prone to diving under cars to collect insurance money, but his real spoils was real estate. Not architecture—he seems to have been something between a middleman and a GC—but flipping properties and leasing them to absentee landlords in order to skirt taxes made his money. This rentier-enriching process helped ruin New York City but made some quick cash for a petit bourgeois in the right place at the right time. Then disappointment hits. Rex’s house gets messy. He builds a vault in his basement to harbor his cheap and unknown tastes. If he couldn’t be Robert Moses, he might as well try being Jack the Ripper. Yet he is finally undone in this basest of ambitions by the fact that even the women he killed might be denied him. Shoddy police work or the incorrect attribution to some other killer—it’s all a question of identity and politics, and no smear on a pizza box is ever foolproof against it.

The doors are still wide open, as welcoming as the courts of law or the gates of a zoo. It doesn’t matter that shows like The Killing Season or Unraveled: The Long Island Serial Killer didn’t get it exactly right. At the end of several hours, after watching the crimes unfold in newscast footage or in jump-cut reenactment, a warm sensation washes over the viewer. This strange pleasure lies not so much in sympathizing with the butcher as he moves over the beach but in another manipulation of time. Over and over again, with each installment and repeat viewing, we know that any escape from the denouement of this synthesized drama will always come to nothing but will again return to tantalize us. There is more: that whatever was begun, beloved, seen through and planned, no matter how close or far from being fulfilled, whether a daydream or paid by each paycheck, everything which transpired before that night—time wherein the mildest moment yielded ecstasy, the most banal became a solitary acceptance of all troubles, fleeting thoughts the most penetrating of human observations—such moments, and we will always have the pleasure of fantasizing about them, are a gift to the dead we imagine we would save. Then, the far greater pleasure of watching every one of these dreaming inventions die in ruin, as if this bloodsoaked ruin were revenge against an intruder who dared to demand more than the meagre fabric we so graciously gave to conceal her. Ryūnosuke Akutagawa describes this quality of mercy best:

The human heart harbors two conflicting sentiments. Everyone of course sympathizes with people who suffer misfortunes. Yet when those people manage to overcome their misfortunes, we feel a certain disappointment. We may even feel (to overstate the case somewhat) a desire to plunge them back into those misfortunes. And before we know it, we come, if only passively, to harbor some degree of hostility toward them.

The Long Island killer case being solved is now openly unsolved, whereas when it was still open, it seemed gray and truncated, its reach decidedly shut off and its outlines opaque. Clarity brings new phantoms. Everyone gets something out of it. The viewer can even feel a little less safe for the duration of the show—a not unpleasurable feeling, if it doesn’t cause one to reflect that the right to safety has murder at its heart.

To the memory of Diamond Jack, who always cracked the case.