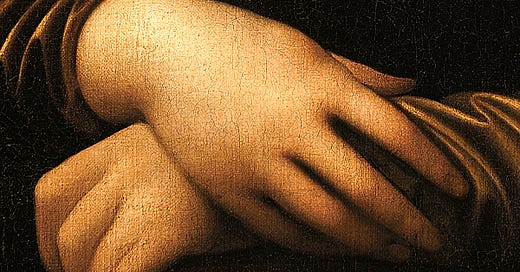

After the first breath is exhaled, the first clench of hands grabs the air. In a few moments these hands will grope wildly, feeling the space around, the wide and colder expanse—and so a child came into the world. Hands speak over the initial cry, without language and without belief and without pleasure or pain. Later, there will be meanings and sensations, but for now there is just the pure unalloyed gesture. This is the only time in one’s life when things are nameless. Human words convey nothing more than the sounds of mice scratching behind a wall or a drop of water on a metal basin.

It’s no wonder that Palmistry has had such a long pseudoscientific life. What better place to predict the future and interpret the past? Long lines, broken lines, threads and streets crossing and crisscrossing. A scar adds an element from concrete history to the accidents of the palm’s folds and creases, a comma marking a subordinate clause in days and years. You would think Palmistry would really work. Isn’t all of life right there? But we look only for trouble and find it after the fact. How long will I live? – alas, the most popular question. Does anyone ask: How well will I live? How well will I die? The answer lies somewhere between the open palm and the fist.

The Hindu sage Valmiki wrote the first treatise on Palmistry over 5000 years ago, scribbling away on his off-hours from composing the immortal epic of the Ramayana. Stanza 428 admonishes us to ‘Keep the hands clean before anything else. Watch the dirt under the nail. When you hold a woman’s hand, you hold her child’s; when you let go her hand, your life points down to earth and worm.’

It was said that the great painter Wu Daozi had the ugliest hands in China. Because he suffered this genetic accident at the wheel of Fate, the Gods took pity on him. After he painted his first canvas, it was said that the hands of Wu Daozi were the most beautiful in the world.

I once sat next to a very small woman on a plane. I thought at first she was a child. She had hardly any legs at all and one of her arms was significantly longer than the other, concluding in a gnarled and twisted balled-up claw. But when performing ordinary tasks like picking up a cup or turning on the seatback screen, her arm and hand moved with a strange sensuality and grace that equaled the most skilled and agile of dancers.

The hand of Adam and the Hand of God almost touch in Michelangelo’s famous fresco at the Sistine Chapel. It is a very odd work. Adam looks bored. God seems to be straining, surrounded by children, his other arm enfolding Eve. But is it Eve? We just suppose it is. It might be Lilith, who was Adam’s first wife according to Jewish legend. The name Lilith, lalit, means Night and Spirits. Refusing to accept second place before her be husband, Lilith fled the Garden of Eden and was demoted to the role of an outcast demon. In Michelangelo’s work, Adam has an extra rib which means that Eve was not yet formed. And as the hand of God has not yet touched Adam’s, the events of Creation remain a potentiality in the Divine Will. Creation begins with hands touching, connecting what is above with what is below. And afterward, the first prohibition and the outstretched hand of the Law.

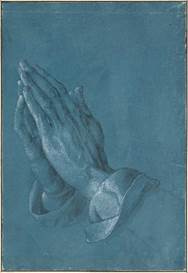

Dürer’s Praying Hands form a steeple. One of the fingers has not yet closed in uniform with the others. Was the finger broken? Maybe this was a heretic’s hand, cupped in repentance after some cruel act of official torture. Or was the story of the broken finger the story of the life of this aging man, hidden in a detail no one would bother to notice? He grasped at the branch, broke branch and finger, then fell into the river. Several feet ahead in the water is a flailing hand. As he wades in deeper, this man who also cannot swim becomes paralyzed by the terrible events as they unfold. He cannot move or even open his mouth. His daughter sinks down and does not come up. Later, in old age, the man prays that God might sentence him to relive this scene over and over again in Purgatory. He is certain that his salvation depends on its expiation through repetition and that on the last repitition, however long it may take, he will be permitted a second chance. He was brave in war. He was kind to his wife. He fed the needy. And so on. But that moment at the riverbank overwrote every good deed in the Book of Life while making every sin seem negligible in comparison. Seeing his broken finger every time he picked up a hammer or prepared for sleep was therefore a curse he willingly accepted. And also, in a tortured way, it returned his daughter to him. He began to train himself to find moments of great joy in his life as well, time spent at his daughter’s side, her young crooked smile resembling the line of his offset finger, the sound of insects in the air and the moonrise. Soon, the finger became the very signature of a vow. And finally, as the moment of his death drew near and crowded over him, the bent finger grew out in its noonday shadow and touched the shadow of the dead girl’s hand. A substitute for a moment that did not occur here on earth—that moment when he saved his child from drowning, where his hand now extends, the hand of a man dying alone, a hand which takes her hand in his. Albrecht Dürer drew the hands of his old friend as a preliminary sketch for what was to have been a major work, a larger canvas which was abandoned for financial reasons, the cartoon of the two hands remaining to become, for some unknown reason beyond the rather commonplace subject of religious devotion, one of the German painter’s most well-known and admired compositions.

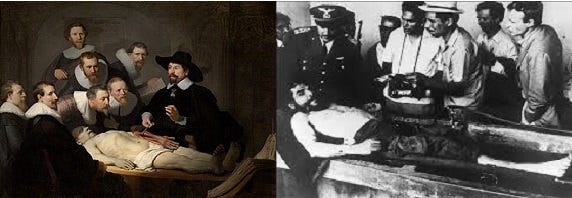

Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp has a curious hand. Anatomically impossible, the hand is upturned as if it had been severed and placed palm-up while the bones of the arm remain natural to the position of the body. The main subject of the painting is unknown, but he may have been that of an indigent or beggar. To show that this is the body of a man of the oppressed, Rembrandt has placed his hand as if it were requesting alms post-mortem. Around him, the experts crowd and see only a specimen where once was a man, a man rushed to an early death by poverty and now employed to investigate complex maladies rather than the common aflictions of the poor. Useless in life, the medical establishment and its donors have given him a purpose and appointed for him an unmarked grave in Potters’ Field. But Rembrandt has laid him out like the Christ, giving this anonymous man the ability to rise from the darkness of time and level in his acute passivity a solemn accusation his torturers can never answer.

It has been noted that one of the most famous photographs of the slain revolutionary, Che Guevara, bears an uncanny resemblance to Rembrandt’s painting. The doctors are now the fascistic goons of the Bolivian police state and a cautious CIA spook who hovers at the edge of the frame; they are assembled at the opposite end of the room while the subject of both images remains the same. The hand that once raised a fist in honor to the beggar’s hand later, quite inevitably, took up a gun. It is also clear from the photograph that Guevara had become a saint. His murderers have been forced to venerate and crowd around him as if they had just rolled away the stone and stand waiting for their Savior to arise and walk again upon the waters.

In the classic 1924 film, The Hands of Orlac, a mad doctor grafts a pair of hands onto the great pianist Orlac after the artist’s hands are apparently mangled in a train wreck. In love with the musician’s wife and money, the doctor convinces him that his new hands once belonged to an executed murderer and thus, Orlac will be compelled to continue the dead man’s terrible crimes. The film’s loopy conceit leads to a number of suppositions. First and foremost, that memory resides in the hands and not the mind. Feelings and touch contain everything—in every ligament and every hair, every lived moment is stored away just below the skin. There is no such thing as immaterial memory; all of one’s history is a series of sensations and reflexes. And if the hands remember and react, then the whole body does so too. Orlac’s feet could have been replaced by those of a great (or notoriously awful) tap dancer. His stomach switched with a gourmet’s or his legs with those of a brilliant tightrope walker. But sadly, none of this is true. On screen, the denouement sees the doctor unmasked as a blackmailing fraud and Orlac, whose hands were not really ruined at all, laughs at how dumb he was to fall for such a load of crap. Doubtless, he will resume his career and play the same repertoire over and over again like a broken record, touring drafty concert halls and making music for wealthy people who couldn’t care less. Real life has similar obsessions with musical hands. In order to explain the great dexterity of the extraordinary pianist Glenn Gould, specialists have come to the conclusion that he suffered from focal dystonia, a neurological condition which affects muscle control. And so the neurologists and biomechanists sound like mad doctors bent on pathologizing the world, explaining everything away with cramps and spasms and synapses ill-met.

The hands of the dying do not want to grasp a fading world so much as another hand that will also lose touch with the world one day. To hold difference and similarity at the same time. To say: I know when one is dead, and when one lives. Making this distinction, the hand holds as tight as can be for the final moments. When it gradually releases, the distinction between the living and the dead is also released along with all other properties handled in time.

And if one has no hands? By war, by birth deformity? Then the air where the hand should be tightens with the pressure of a phantom limb, closing around the warm hand that has come to touch farewell. The hand of the living closes in sympathy with the dier’s hand, the two of them knowing that they hold onto nothing but also that they have held nothing back.

Sign language is the most profound of all tongues. It knows that the sound of words in itself means nothing, which is perhaps why the deaf smile so frequently as they communicate. Signing gestures linger in air like cigarette smoke, tracing shapes and scenes in the atmosphere, pulling events and concepts out of thin air and transcribing the invisible revolutions of the mind. Anyone can learn sign language and enter into this elite world, but only the highest live in complete silence. Sign language is closer to thought that words; the signers seem to be almost telepathic. Words are geese, car horns, just a load of screaming. And who needs to hear Mozart anyway? You can look at the score and imagine a far richer work which no one has ever heard, a Mozart whose real music sounds lower than a mouse.

When the time comes to depart, I won’t argue. My hands once held an orange. They picked up a little bird which had fallen to the ground. I knew people that had lived as well if not so long. What is left to be done after all that? What is only worth seeing?

God’s hand guides your writing, brother Martin. It is impossible for me to convey all this means to me and to those others who will receive this gift.

Thank you Mr. Martin Billheimer (: Hows Chicago treating you?