In a letter dated January 8, 1782, Elisabetta Caminer Turra, publisher of Voltaire, polemicist and dramaturge, takes issue with a journalist’s description of her native Venice as ‘peopled with uninhabited houses… rooms thick with ghosts.’ According to her, Venice’s houses are not filled with the spirits of the dead but with an absolute void: There is nothing about them that calls to a part of me which would describe them in words that noted or even hinted at a populous. She goes on to attack the writer’s sense of the past as measurable only by humanity’s presence in time: If these walls could talk, they would anyway be too old to remember any thing. The city’s buildings resemble the figure of a decrepit king on a throne being controlled by a high priest… dormant and cold. People become buildings. Buildings forget their people. There are no ghosts, just a great stony silence.

For Madame Turra, all this talk of haunting is a cheap shot. Her far more radical vision is of a city seen from a point in the future when all knowledge of its practical life has been lost. By choosing a concept seemingly drawn from art—things existing only for their own sake as phenomena, the riddle of inscrutable features on a canvas—she finds in all this talk of specter-haunted villas and vast Piranesi-like manufactory an unspoken admission that a world without humanity is impossible for humanity to conceive. The Enlightenment she vigorously defended in her political tracts is too cowardly to confront the accusation it rightly leveled at superstitious clericism: though you have power and agency, you are not the center of the universe. She realizes that the face is not the depth; the image does not depend on the observer; the spook is the viewer, rarely the object.

Looking at the Surrealist paintings of Magritte and de Chirico, where houses are depicted as flat and impenetrable, it is hard not to think of Turra’s amnesiac buildings. Their real-life correlation is not found in architecture but the theatrical or film set, where only the façade is real. When we watch a movie, we do not immediately think that its sets have been recycled many times before. The actors haunt our memory because we have seen them in other films, costumed as Pharoah, a wino, a prostitute, or a cyborg. It is the sets that truly reappear like magic, propelling the cast backward or forward in time, aided by editing and the audience’s imagination.

The uninhabited is not the uninhabitable. Madame Turra’s urban landscape has not so much been abandoned as left to its own devices. The population may have departed but when they went, they left nothing of themselves behind. This latterday city looks like a set of false teeth posted in a human landscape, puzzling additions to a body long since rendered obsolete.

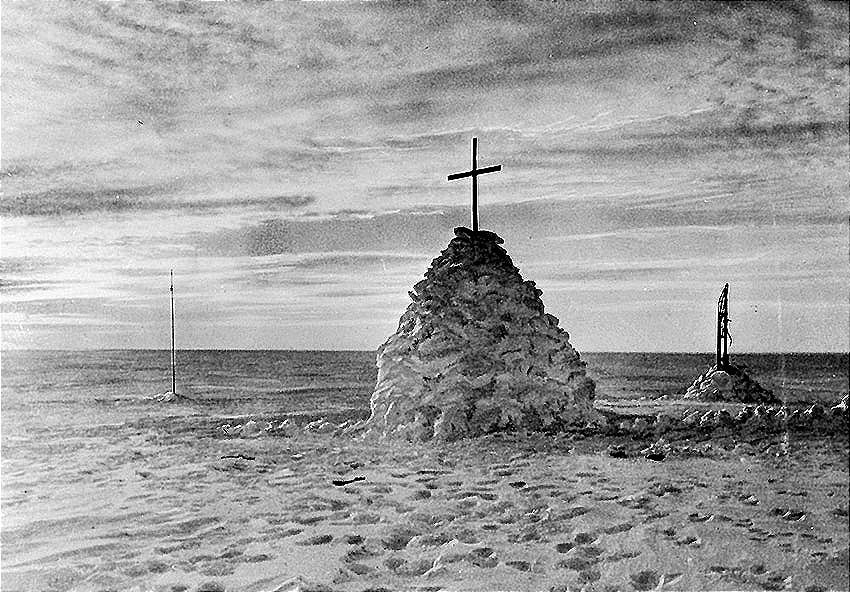

Making a place uninhabitable is a magical transformation, done seemingly by the will of God. Human agency is covered up by the passive tenor of the word. Martin Griffiths, UN Humanitarian chief, called Gaza ‘uninhabitable.’ Yet it is assuredly inhabitable because it is inhabited, despite the best efforts of the genocidaires. Scott and Amundsen found people in the supposedly uninhabitable arctic wastes. Scott must have been convinced these figures were ghosts, because he ignored their advice and died as if he were inhabiting a dream [i]. Amundsen listened, kept wide awake, and lived to tell. Strangely, the explorer is always surprised when he stumbles upon life. These people cannot possibly survive here—the statement of a provincial, for all his masculine intrepidness…

In time, the explorer is followed by settlers. The settler risks being twice homeless, twice evicted, which drives him to a frenzy. For the settler, every land is uninhabited until his shadow crosses its fictitious borders. He transforms what he first saw as wasteland into the inhabitable and generous. Like the explorer, he is confronted with strangers in these empty places—the living reminder of an abject terror, that he does not know where he is. To prove his superiority, he claims that these indigenous are slaves to animism and magic fetishes, but his own drive to erase them—and thus become them, in the present but also in the deep past—is the very definition of primitive sorcery. Another existential fear of the settler: That he does not really exist, that he is nothing without what he constructs to fend off this gnawing absence. He must build, rename, expand, annex, make bloom: all in order that he might know who he is by knowing where he is. Like Captain Robert Falcon Scott, the settler is in Antarctica but not of it.

When they first encountered the menhirs and the great structures such as Stonehenge, the invading Anglo-Saxons thought these ancient stone works were made by giants. More recently, the popular idea is that megalithic monuments are high tech mysteries left behind by space beings. Questions of the use of these places dog every opinion from the sober to the wildly unhinged—that they have no purpose is quite inconceivable. Ghosts of the future throng ancient places, and like senile tour guides they ask us to explain these mysterious locations. Is it possible to be sick of hauntings? That a place might become metaphysically overcrowded? Signora Turra’s statements above show a prescient exhaustion: she suspects that her descendants will create a pornographic nostalgia industry around ruins and populate them with selfish invisibles from the past.

When the utilities of a house have been cut off, City Hall declares it uninhabitable. Through nonpayment on light and heat, every room quickly becomes lifeless. Weird idiomatic expression: There is no one home. But that is impossible!

Whether the universe is uninhabitable save for Earth is a big question, depending on what one considers to be life. The idea that nothing can have a kind of soul or spirit unless it is touched by humanity unites both the religious and the atheist. Yet isn’t the idea that a universe, extending infinitely everywhere but having no other intelligence, indescribably beautiful? Despite the infinite possibilities of minute repetition, everything happens only once. Life, the animal kind, is just another detail along with the dust of a comet or the temperature variants of suns. How to describe it all? I cannot see you without seeing myself—a tragedy, there is no other tragedy and no one but yourself to blame.

[i] Curious to note the popular conceptions of drowning and freezing to death as comparatively painless ways to die. Slipping off like into a dream, held by water or snows, a final shiver then the realization: I am leaving life. Leaving, and all sense of direction is lost.

A brilliant essay, perhaps his best! It brings together many threads and manages to tie the right knots. It is an essay that makes you think, and you can say nothing better of an essay than that. Turra's letter was dated 1782, which means that the Republic of Venice had another seventeen of life. In 1799 Napoleonic France and the Hapsburg Empire decided that its territories were an appropriate place to have a battle and it was clear that whoever won would also annex the patrician republic, which was, it's true, a declining power both militarily and financially. While Britain and France generally dominated trade in the Mediterranean in the eighteenth century, Venetian merchants had increased trade during periods of warfare between those two powers, because warfare entitled one power to seize the shipping belonging to the other. No doubt it was no longer the wealthy and bustling place it had once been, and yet it was still no slouch. It was a city state that exploited his small empire (la terraferma) and had its own language and literature behind it (Venice was responsible for choosing what would become the Italian language, and they didn’t choose their own but Tuscany’s or rather the literary language established in Tuscany in the fourteenth century two centuries earlier; they did this not out of nationalist verve or desire for Italian unification but to create a larger and more reliable market for Venetian printers – it was that kind of place). It had the highest percentage of owners of musical instruments and was still the centre of the European musical tradition but, like Britain, it was that declining power that refuses to face reality, and I can well imagine that someone like Turra would be in a hurry to leave behind her this stuffy and conventional society unable to defend itself and yet certain that it was still the centre of the globe. She went to the real centre of original thought which was France and she joined the most radical stream (it seems, because I hadn’t heard of her before reading this essay).

I write all this because the argument between her and the journalist demonstrates how prophetic both of them were – her even more than him – because their observations only became reality in the last forty years. Today it is absolutely a city of empty houses owned by the world’s elites and visited by themselves very rarely, but demand means that their assets are increasing in value every year. The population of the city has moved to Mestre and other anonymous dormitory towns surrounding the lagoon, and many of them will be commuting into their old home city to provide services to the endless stream of tourism. After the war, the rent freeze made the population safe for some decades but as people grew old and died, those flats would enter the “free” market and disappear forever from the reach of its local population.

Billheimer takes this original argument into a fascinating exposition on the relationship between humanity and its built environment along with the most important argument of how Western settler colonial societies interact with indigenous peoples – or rather don’t interact but despoil and annihilate instead. But I wanted to add a coda on Venice today as seen by Italians who call it “Disneyland”.

Another fine, fine piece. Bravo!