Exhaustion

"And it was at the hour of sunset that they came to the foot of the mountain...."

On May 1st 1823, the Italian chemist and naturalist Nicola Covelli visited Mount Vesuvius to collect samples of volcanic mineral deposits. By analyzing residual traces of ferric oxide and calcium sulfate in the surrounding rock and scoria, Covelli hoped to calculate the temperature of the lava that had poured out of the volcano on that fateful day in 79 AD, engulfing the nearby resort towns of Pompei and Herculaneum with molten fire and blackening the sky over Rome with a great cloud of ash. He set out in the morning for a leisurely hike to contemplate these catastrophes of geology and history.

Lost in reverie in the hills, Covelli suddenly realized that he was also physically off-course. It was not his first trip to the site and the environs of Vesuvius are not particularly treacherous, yet when he looked around to get his bearings, nothing looked at all familiar to him. It seemed, he wrote in his diary, that he had entered a sidereal zone which ‘had a devious feeling about it, as if I had chanced upon an area that was somehow unfinished by God.’ The more he contemplated his weird position, the more he became convinced that some genius loci was playing tricks on him. He thought of those famous words of Dante: la diritta via era smarrita.

Covilli then describes a wave of utter physical exhaustion which flooded over him, making it painful for him to undertake even the slightest movement. His lifetime fascination with igneous rock and geochronology became in his mind, so he says, a terrible revelation that the whole universe was an impenetrable granite block inside of which humans moved blindly along in a tiny coal seam. As the noon fog rolled in from the Tyrrhenian Sea, the distant towers of Naples disappeared into the haze and the underbrush around him seemed ‘frozen in midmotion.’ No birds sang, no breeze came in from the waters, yet there was a paradoxical ‘frenzy of movement’ in the air, as well as a strange foul-smelling musk—the latter, Covelli notes, reminded him of the odor of mink. Seized by an all-encompassing despair, he decides to make for a small copse before he might collapse.

Within seconds of entering the clearing, Covelli felt a tremendous sense of relief. Having an almost ‘home-like’ (accogliente) quality, he says, the area, unremarkable in itself, seemed to act as an immediate palliative to his highly disturbed state. It was as if a life-giving sap flowed directly into his muscles, giving him a profound sense of peace and the certainty that he would find his way back. Covelli stood up and began to walk briskly toward a small ridge which, he reckoned afterward, was about a kilometer away from the clearing. On the other side of the crest, Covelli saw the head of the metal centaur of Pompeii glinting in the sun, the road winding down to the docks, and a few figures on the pier unloading light scientific equipment from a skiff.

This whole experience takes up a paragraph in Covelli’s otherwise mundane field diaries. Though an observant Catholic, he harbored anticlerical sympathies (Covelli was associated with the Carbonari, a revolutionary republican order, and this had cost him a job in Naples). The idea of the intercession of the saints does not occur to him; neither does he mention spirit guidance from the Roman dead or the nymphs of Diana. Instead, Covelli posits the idea of a ‘landscape that exists in a different order of life’, though he does not elaborate on this concept and attributes his survival to his wife and family, the thought of whom, he adds felicitously, sustained him throughout the ordeal. The closest Covelli comes to metaphysics is a reference to a ‘spiritual fog’ which overtook him as his limbs stiffened and his mind turned despondent. The will to life can dissipate and, he fears, may not return no matter how great the internal effort, like when ‘one is drowning and knowing this beyond a shadow of a doubt, slowly relinquishes everything to the depths… sinking down in the waters of an indeterminate state which must feel so like sleep.’

Sometimes the place of refuge is a figure. The Arctic explorer Ernest Shakleton had the sensation that a fourth man was accompanying him and his two companions as they trekked through the snowbound wastes. Such phenomena are usually explained away as coping mechanisms, tricks of the brain to fend off hopelessness in life-threatening circumstances1. But this salvific presence seldom returns in a person’s life after the great adventure is over. Shakleton’s comrades lived only to die in the trenches of the Great War several years later. Drawing ever wider apart, the shipwrecked and the stranger cease to recognize each another. Life goes on to other things.

The concept of a sentient landscape continues to haunt geologists, though it is embarrassing for any scientist to admit it. It is not so much an anthropomorphism, but a suspicion that the earth might possess a category of being we will never be able to comprehend. Yet perhaps some of us already do. In the Shinto religion, for example, being is not limited to plants and animals. The presence of an object affects the observer and the observed, giving it its own aura and its own unique features. This is also true of places. You can mourn a rock just as you mourn the loss of a beautiful tree or the departure of a friend.

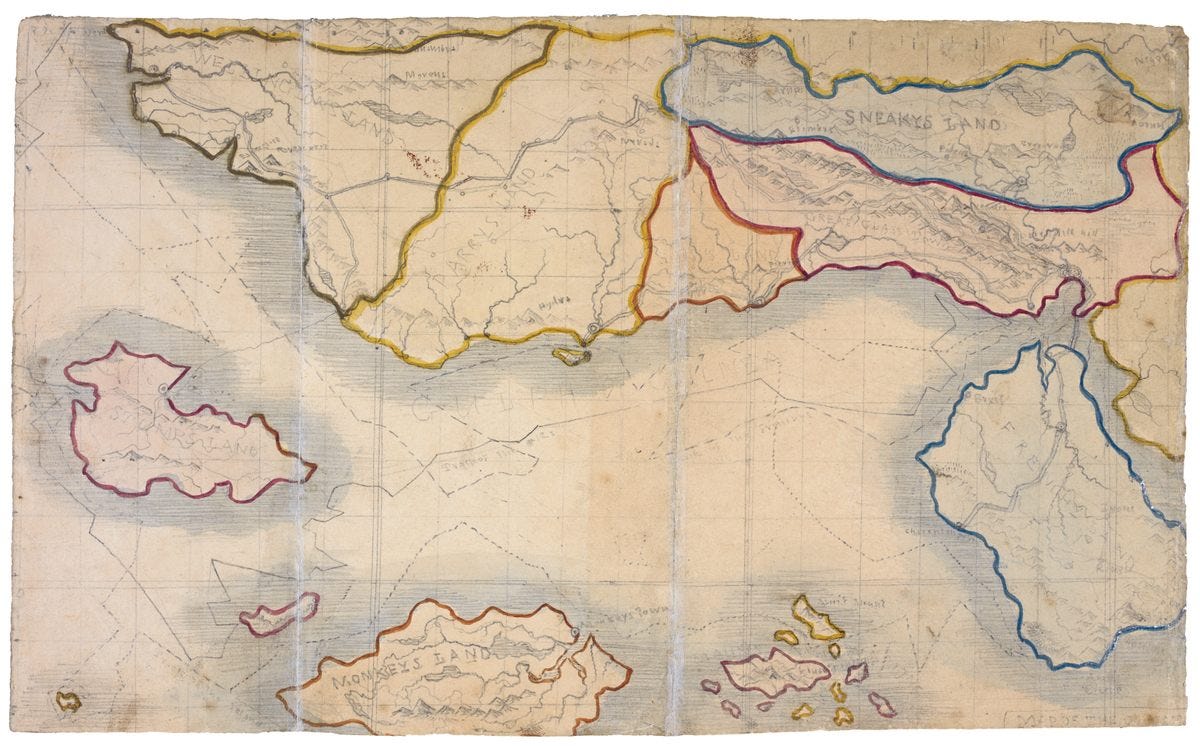

It would be fascinating to attempt a new kind of cartography where places are rendered by the sensations they invoke, sometimes influenced by human events but also by more complex powers. A sensational topography for use in everyday explorations, complete with warnings in the case of sinister zones and directions to locate rejuvenating spots if one becomes lost, even though the map always shows you exactly where you are.

But those who are not so lucky, do they feel a similar presence at the end? As it guides them in another direction, no doubt with the same stoicism and perhaps with comparable charity, these doomed souls leave behind a few banal notes or a cryptic log entry. Of the penultimate moment, the psychological state of a final giving over, they say nothing at all.

Very interesting, remind me of https://hermetictardigrade.substack.com/p/tallulah-fairyland

Most fabulous essay, I read portions on the air (Visionary Activist Radio Show just now)- with attribution, bien sur... Thankyou...